Detecting and protecting the Kangaroo Island dunnart

Monday, 24 September 2018After five months of trapping, it was our last night attempting to catch a Kangaroo Island dunnart. At about 2.30 am the rain hit, sending big sheets cracking against the tin roof of the research station. Alex and I pulled on our rain gear and stumbled down the driveway to faithful Betty, our red Hilux ute. By the time we’d arrived at the site, the pitfall traps had about a foot of water in them and for the first time in a long time, I was relieved to not find anything in the pits but a few fairly happy frogs and a precariously balanced stick insect.

Catching a Kangaroo Island dunnart was never going to be an easy task. When we started the project in April 2017, they had been seen at only eight sites on western Kangaroo Island in the past 20 years. Extensive survey work in 2001 suggested they breed during early summer, eat mostly insects, and sleep during the day in hollow logs and in the skirts of ancient grass trees.

Across Australia, feral cats are recognised as a key threat to wildlife. Kangaroo Island is one of five Australian islands where islanders and government agencies have begun the task of eradicating the pest.

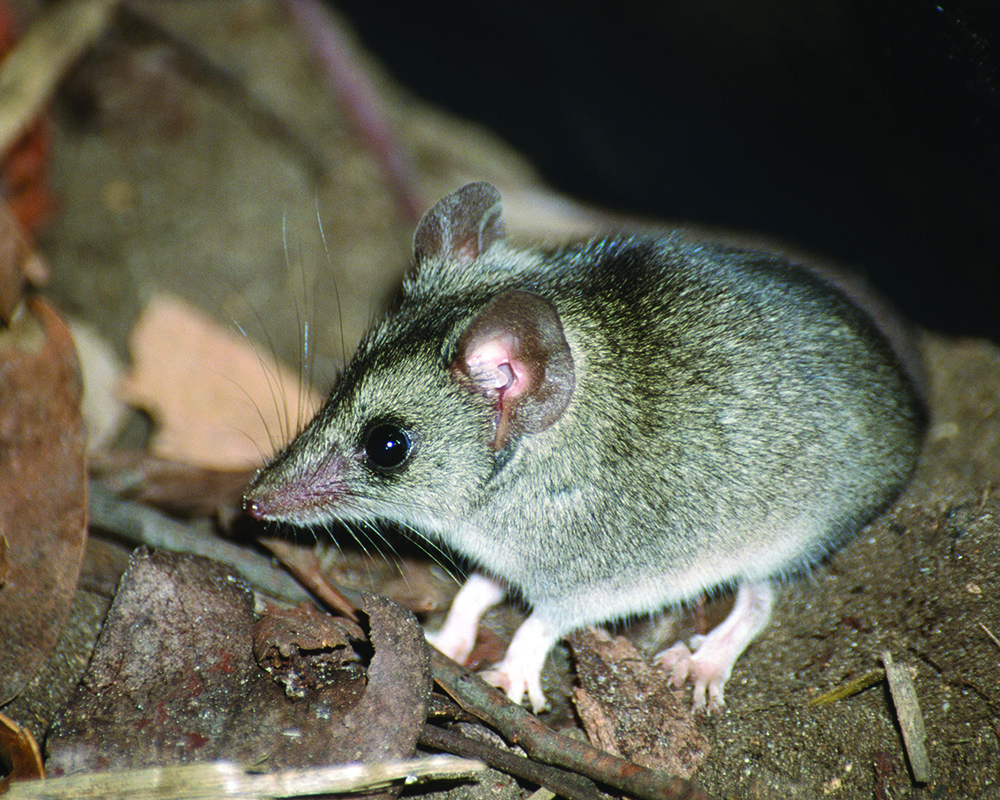

Kangaroo Island dunnarts are visibly distinguished from other small mammals by their pointed snout and wide, almost square-shaped, ears. Photo: Jody Gates

To help out with this ambitious objective, we were interested in understanding how cat control would impact the Kangaroo Island dunnart. As the last extensive survey work for the dunnart was done almost 20 years ago, we hoped also to use some fresh detection methods to assess their status today, find them in some new locations and learn a little more about what they need to survive in the landscape.

For five months in 2017 and 2018 we trapped for dunnarts at 42 sites across western Kangaroo Island using four methods:

• Pitfall traps (three sizes)

• Elliott traps (metal box traps)

• Camera traps facing fence lines

• Camera traps facing baits

Pitfall trapping of course requires a lot of digging holes, digging trenches and rolling around in the dirt. That said, we caught a lot of wonderful things. Pygmy possums were a particular delight, as we often found them on cold mornings curled in a tight furry ball as the bottom of the pit, and we’d pull them out and slowly warm them up in our mittens.

We detected dunnarts on camera seven times at five sites. Four of those sites were new, previously unsurveyed sites, and one site had a historical record. Unfortunately, dunnarts were not detected at six of the seven sites with historical records. Camera traps placed to face long, heavy duty plastic drift fence lines were the most effective detection method.

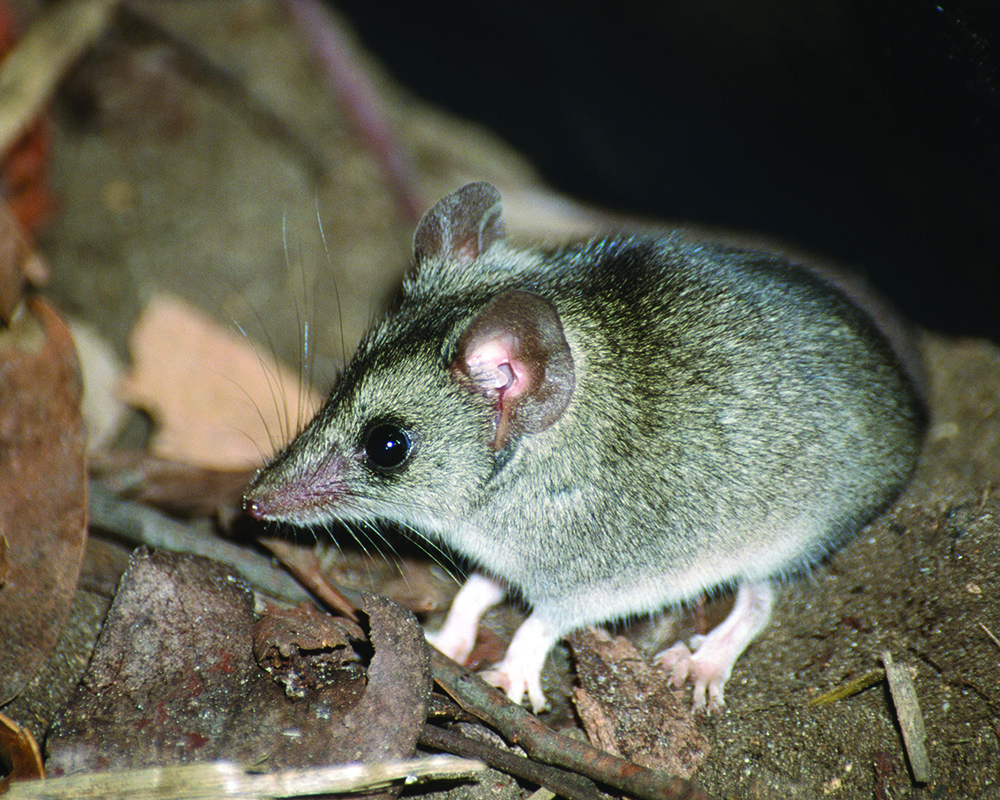

An infra-red camera trap image of a Kangaroo Island dunnart. Photo: Rosemary Hohnen

An infra-red camera trap image of a Kangaroo Island dunnart. Photo: Rosemary Hohnen

Although our pit traps failed to catch our target species, we found that wide deep pits were most effective at catching other small mammals such as native bush rats and western pygmy possums. This indicates that if dunnarts need to be caught, for example, to collect genetic samples, wide pits are likely to be the most effective method.

From our camera traps we detected dunnarts in recently burnt (0–10 years post-fire), regenerating (10–20 years postfire) and long unburnt habitats (>20 years postfire), so there was no evidence the dunnarts prefer one particular age of post-fire vegetation. They were detected most frequently at open low mallee sites dominated by Kangaroo Island mallee ash (Eucalyptus remota), but also at one open woodland site dominated by messmate (Eucalyptus obliqua).

We are currently conducting a more detailed analysis of habitat preferences.

We also assessed the density of feral cats in the region, to understand the extent to which cats might threaten the population, and provide information to support the planned cat eradication. Arrays of 50 remote infrared cameras were deployed to detect cats in farmland, at the border of the national park, and within the national park. On the border of the forest and farmland the density of feral cats is 0.27 cats/km2, similar to the mean density on mainland Australia. The arrays deployed within the park and on farmland are still being analysed.

In August this year, we’ll also start the final stage of the project where we’ll examine how broad-scale feral cat baiting will impact resident small mammal (‘non-target’) species. Currently 1080-based “Eradicat” baits are the only commercially available, feral cat-specific bait in Australia. Feral cat baiting is likely to be used in the national parks of western Kangaroo Island as much of the park is inaccessible by road, and baits can be dropped aerially in these areas.

Some small mammals on western Kangaroo Island have a reasonably low tolerance to 1080 and there is a possibility some could die if they eat a sufficient amount of the feral cat baits. We currently don’t know if small mammals will eat the baits. To test this, we will use non-toxic baits that contain a biomarker called Rhodamine B. If an animal consumes a bait, the harmless Rhodamine will be deposited in the animal’s whiskers and will be visible under UV light. So by taking whisker samples from resident small mammals, we will gain an idea of the proportion of the population that has potential to be impacted by toxic baiting.

Overall, we managed to detect Kangaroo Island dunnarts at five of the 42 sites surveyed, suggesting they may be in low numbers on western Kangaroo Island. Feral cat control could potentially really benefit the species, and hopefully the results from the non-toxic bait trials this year will allow us to determine the feasibility of broad-scale feral cat baiting, which may be an important tool in supporting this species’ persistence in the future.

The project is being led by Charles Darwin University, working collaboratively with:

SA Department for Environment and Water; Natural Resources Kangaroo Island; Australian National University, the University of Queensland, the University of Sydney and the local Kangaroo Island community.

For further information

Rosemary Hohnen

rosemary.hohnen@cdu.edu.au

Top image: Volunteers Sarah Leeson and Alex Hartshorn sit down to weigh, measure and identify animals caught at a trapping site on western Kangaroo Island. Photo: Rosemary Hohnen

Rosemary Hohnen

rosemary.hohnen@cdu.edu.au

Top image: Volunteers Sarah Leeson and Alex Hartshorn sit down to weigh, measure and identify animals caught at a trapping site on western Kangaroo Island. Photo: Rosemary Hohnen

Related Videos