A golden opportunity realised, but so much more to do

Sunday, 12 December 2021Professor Brendan Wintle,

The University of Melbourne

Threatened Species Recovery Hub Director

The extinction crisis, like all of society’s most wicked challenges, is daunting. However, unlike other existential threats such as climate change and pandemic, biodiversity loss has yet to attract financial and policy commitment that is adequate to address what is now a global crisis.

That is one of the reasons why the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, which was supported by $32M from the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program and $40M in contributions from hub partners, was a unique and critically important opportunity to deliver science for saving Australia’s species.

We were given six years to provide the science to improve the outlook of (over 1800) threatened species. No pressure. After 147 research projects, we have arrived at the end of an incredibly challenging, exciting and fulfilling journey. Together, the efforts of 260 staff and researchers, including 77 postdoctoral researchers and 82 students, collaborating with 250 wonderful partner organisations, including 65 Indigenous groups, has transformed science, influenced policy and raised the profile of threatened species.

You can explore the findings of this incredible body of work on our website. At the national level this has included things like identifying our most immediately imperilled species to provide time to act, a threatened species index adopted as a core national biodiversity indicator and new state policies for biodiversity sensitive urban design.

But the issues confronting many species are local and for these we have delivered more than 100 on-ground collaborative projects, such as Martu-led monitoring of mankarr (bilby), award-winning cross-cultural conservation planning and IUCN Green Listing at co-managed Arakwal National Park, support for Kangaroo Island’s post-fire recovery planning, genetic modelling to help inform mammal translocations to Dirk Hartog Island, and greatly improved detection methods for a range of cryptic species and new knowledge on their distributions.

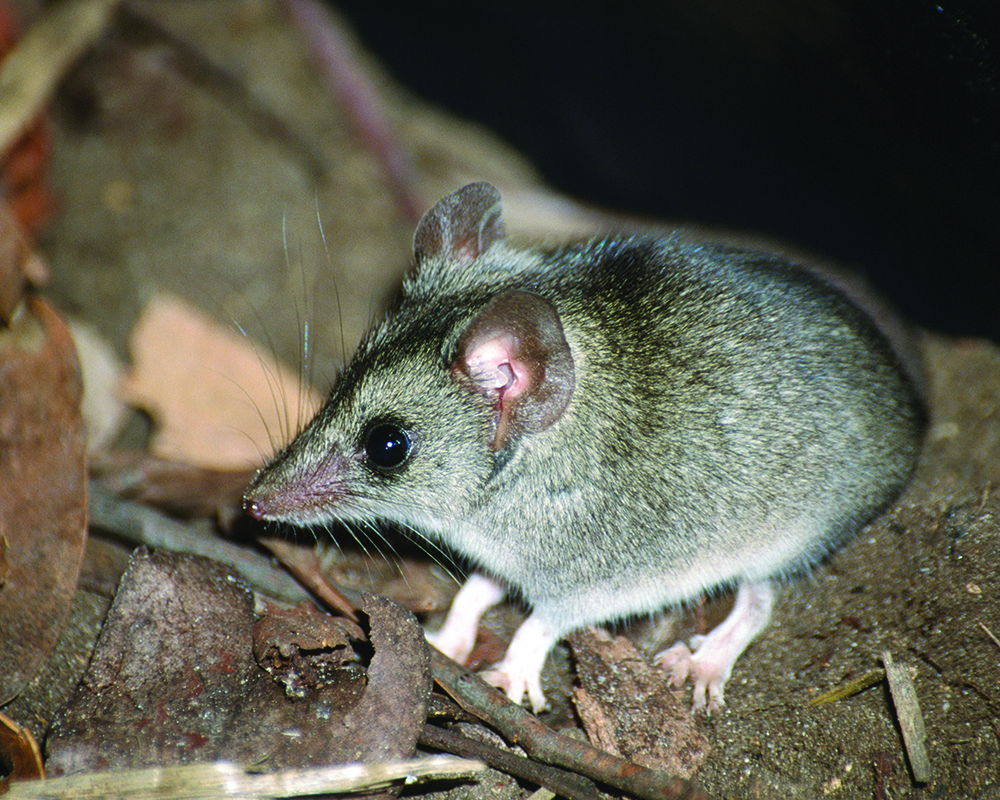

The Kangaroo Island dunnart has greatly benefited from hub research led by Charles Darwin University which determined the most effective monitoring method for the cryptic species and applied it to extensive surveys. Image: Jody Gates

The Kangaroo Island dunnart has greatly benefited from hub research led by Charles Darwin University which determined the most effective monitoring method for the cryptic species and applied it to extensive surveys. Image: Jody Gates

The relationships we developed with the nation’s land managers and policy-makers have allowed us to do the useful stuff – research with a direct pathway to impact. In many cases, these relationships were brokered or facilitated by our amazing knowledge brokering and Indigenous engagement teams, led by Rachel Morgain and Brad Moggridge.

Our way of doing things included a commitment to engagement and co-design. Research was always done hand-in-hand with those people who want to use it. Each project built networks and relationships, communities of practice, trust and hope that will persist well beyond our hub’s short life. Our way of doing things will live on in these networks and in the early career researchers who have absorbed the hub approach and grown their careers and networks. The Threatened Species Recovery Hub tint does not wash out easily.

The stories of our work have been told far and wide thanks to the skill and dedication of our amazing communications team, led by Jaana Dielenberg. There have been over 7,500 articles in the media on hub research with a reach of over 43M people and an estimated advertising value of $29M (if one was to buy that exposure) and these have made a crucial contribution to public discourse on threatened species.

Research led by The University of Queensland identified Australia’s 50 most imperilled plants, including Queensland’s Capella potato bush, and developed a detailed plan to conserve them. Image: Teghan Collingwood

Research led by The University of Queensland identified Australia’s 50 most imperilled plants, including Queensland’s Capella potato bush, and developed a detailed plan to conserve them. Image: Teghan Collingwood

In addition we have produced over 300 findings factsheets, 140 reports, 147 project pages, 19 magazines and a wide variety of news stories, videos, data, models, prioritisation tools and a book or six. The rapid assimilation, synthesis and presentation of complex data and knowledge into management and policy-relevant information is one of our signatures.

Our immense body of work will live on as a future resource for conservation practitioners, accessible through the highly searchable hub website, as an Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) Biocollection and on the National Library’s Trove platform.

The responsiveness of our hub to the pressing questions of the day has allowed us to make profound contributions, such as was embodied in our work to inform national priorities for bushfire recovery. But we have also shown vision by focusing on some more difficult things that weren’t always directly requested, but rather for which we as scientists perceived the need. I think of offsets policy guidance, the national review of threatened species monitoring, an assessment of bushfire impacts on invertebrate species, and a collective assessment of the actions and resources required to secure our long list of threatened species against extinction.

In Tasmania, Dr Dejan Stojanovic and his colleagues from The Australian National University have delivered a wide range of research to support the conservation of highly threatened orange-bellied parrots, swift parrots and forty-spotted pardalotes. Image: Dejan Stojanovic

In Tasmania, Dr Dejan Stojanovic and his colleagues from The Australian National University have delivered a wide range of research to support the conservation of highly threatened orange-bellied parrots, swift parrots and forty-spotted pardalotes. Image: Dejan Stojanovic

Swift parrot chicks. Image: Dejan Stojanovic

Swift parrot chicks. Image: Dejan Stojanovic

Our submissions and presentations to every major biodiversity policy and legislative process ranging from the Faunal Extinction Senate Inquiry and Graeme Samuels’ EPBC Act Review to the Feral Cat Inquiry have changed and led narratives and we are confident that they will continue to contribute to improvement in national policies.

I would like to extend my immense gratitude to our Steering Committee, led skilfully, diplomatically, and charmingly by Steve Morton. Our Indigenous and stakeholder reference groups also donated to us so much experience, wisdom, goodwill and guidance. Our incredible core team, led by Christine Fenwick, Heather Christensen, Jaana Dielenberg, Rachel Morgain and Brad Moggridge and their support teams were the spine of the hub. Their tireless commitment to the threatened species cause seemed to propel them so far beyond reasonable expectations. They provided the grunt and the gloss and must own much of the credit for what has been achieved.

Finally, I feel honoured and inspired to have been able to work with a leadership group of such prowess, good humour, and guts – Martine Maron, Sarah Legge, John Woinarski, Stephen Garnett, David Lindenmayer and, for a crucially formative time, Hugh Possingham. I can’t imagine that I will again be part of such a team.

While the tenure of the hub is now complete, there has never been a more important time for brave and committed evidence-based investment in threatened species, co-designed solutions, and frank and fearless conversations.

While our threatened species index shows us that the trend in threatened species is downward, public support is rising. There is momentum for change evident in the media, the private sector and civil society. New leaders will emerge, perhaps driven by the need for nature-based climate mitigation and adaption, and they will need the backing of willing and committed scientists. There is so much more to do.

Professor Brendan Wintle

Top image: Professor Brendan Wintle on Kangaroo Island six weeks after the Black Summer Bushfires to work with key stakeholders to bushfire recovery planning. Image: Nicolas Rakotopare