From the ashes: The 2019–20 wildfires and biodiversity loss and recovery

Monday, 31 August 2020Fire is a complex, important and pervasive ingredient in the ecology of Australia. It destroys life but brings renewal. It can operate within or beyond our control. Individual fires, and the historic patterning of fires, can have severe impacts on many threatened species and ecological communities. And fire can compound the impacts of many other threats. Professor John Woinarski of Charles Darwin University discusses the catastrophic losses of the 2019–20 fires, and how we can move on from mourning to action that can limit such future devastation.

Although fire is an inextricable component of most Australian ecosystems, the 2019–20 wildfires of eastern and southern Australia were way beyond normal. Catalysed by extensive drought and unusually high temperatures, these fires were exceptionally extensive, long-lasting and severe. More than 12 million hectares were burnt over the period August 2019 to March 2020, across forests, heathlands and farmlands from south-eastern Queensland to eastern Victoria, on Kangaroo Island and in south-western Australia.

Conservation setback

These fires killed residents and firefighters, destroyed infrastructure and had severe impacts on many regional communities. Major conservation values were affected, including many national parks, World Heritage areas, wetlands of international significance, and threatened species and ecological communities. In some cases, the gains made from years of painstaking conservation effort were destroyed or significantly set back. Most likely, no other event in our lifetimes has had such a sudden and drastic effect on wildlife conservation in Australia.

Awareness of the catastrophic scale of the environmental loss was seared in community perception by images of badly burned koalas, the charred corpses of kangaroos and vast blackened landscapes, and by the stories told by those dealing with injured wildlife, or scarred by witnessing such loss of nature. The responses by governments, conservation NGOs, landholders and the Australian and international public were extraordinary, and heartening. Much support was mobilised; many injured animals were rescued; some threatened species (such as the Wollemi pine) were expertly protected from imminent fires; and many agencies undertook emergency post-fire responses.

These were critical and timely actions, but there will be a long and arduous road to recovery for many species and ecosystems. The on-ground actions will need to be complemented by overhauls of management, planning and policy informed by lessons learned from these fires. To help frame such a strategic response, the Threatened Species Recovery Hub (with inputs from other researchers) rapidly developed a blueprint for recovery of biodiversity – see Further reading.

Future responses

Unfortunately, government, community and conservation systems were not well prepared for these fires. We need to reduce the likelihood of such future fires; ensure that key biodiversity values are better protected in fire planning and suppression; and be capable of responding even more rapidly and cohesively in the aftermath of any future fires. Building such resilience will be contingent on the manner in which we deal with the fundamental underlying cause of mega-fires – climate change. Unless global emissions are curtailed, it is inexorable that the dystopia we witnessed in the 2019–20 wildfires will recur, with increasing frequency and extent, and with diminishing chances of environmental recovery.

Along with the conservation and research programs of many other groups, many of our projects were affected by these fires. These project impacts have since been compounded by the travel restrictions imposed in response to COVID-19: many of us can’t yet access the fire-affected sites critical for our research and management.

The fires also present important research opportunities. There is much that we need to learn about immediate and longer-term impacts and about what recovery actions are most effective. Major knowledge gaps have hindered our remedial management responses this time; and we should aim to have greater preparedness for any next time.

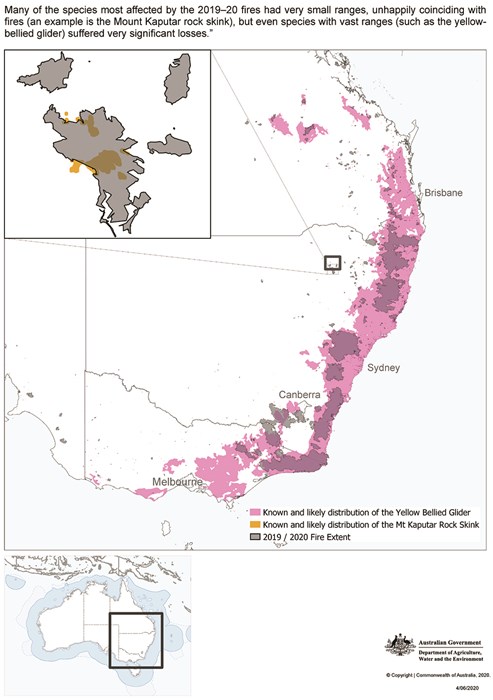

Monitoring is a notable example: notwithstanding many calls to remedy the deficiency, Australia lacks a comprehensive national biodiversity monitoring program. That lack renders it especially difficult to assess the extent of biodiversity loss due to these fires and reduces the capacity to measure the extent and rate of recovery and the effectiveness of recovery actions. Likewise, there is limited distributional information for many species, making it challenging to assess the proportional loss in fires for many species, or to identify key strongholds that may have escaped the fire.

MAP: Geospatial and Information Analytics (ERIN), Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, May 2020

Australian Government responds

The Australian Government rapidly committed $50 million to urgent post-fire conservation actions, with a subsequent $150 million for ongoing strategic responses. Recognising the urgent need to assess the impact of these fires on biodiversity, and that more evidence was needed to help design and prioritise recovery actions, the Minister for the Environment directed $2 million to the hub to undertake a set of priority fire-related research projects. These projects include development of monitoring guidelines; more detailed assessments of wildlife mortality and of the impacts of the 2019–20 fires on invertebrates and frogs; Indigenous involvement in bushfire recovery; development of conservation strategies for fire-affected threatened ecological communities; and many others.

With membership including several hub researchers, an expert advisory panel was established by the Australian Government to assess, at national scale, the national impacts of the 2019–20 wildfires on biodiversity and to help guide allocation of substantial Australian Government funding for urgent and longer-term recovery management actions. Assessments coordinated by that panel have identified 471 plant, 213 invertebrate and 92 vertebrate species that have been most severely affected by these fires.

In most cases, more than 50% of the distributions of these species was burnt; in many cases over 80% of the distribution was burnt; and the entire extent of the known distribution of some species was exposed to high-intensity fire. It may be that the fires have caused the extinction of some of these species, but the evidence is not yet available to demonstrate such an unwanted outcome. Many of the most affected species were highly restricted (narrow range endemics): there are many such invertebrate and plant examples, especially from the Stirling Range in south-western Australia, and from Kangaroo Island. But even species with vast ranges (such as the yellow-bellied glider) were substantially affected by these fires, leaving large formerly occupied areas now uninhabitable (at least for a time) and severely fragmenting surviving populations.

As a consequence of these wildfires, there will be an urgent need to assess or re-assess the conservation status of hundreds of species, to give those most fire-affected species more legal protection and a profile for conservation management. Many threatened species are now far more imperilled, and many species we formerly considered secure can no longer be presumed safe. The 2019–20 wildfires caused a loss of extraordinary magnitude to Australian biodiversity.

Our challenge is to go beyond mourning that loss, to instead work even harder and more strategically for recovery; to help shape a better future for us and our environments – a future that is more resilient, and less likely to experience another such catastrophe.

Further reading

https://www.nespthreatenedspecies.edu.au/_images/Projects/After%20the%20catastrophe%20report_V5.pdf

Further information

John Woinarski - John.Woinarski@cdu.edu.au

Top image: Green shoots emerge after an early season burn on the Tiwi Islands. Image: Nicolas Rakotopare

-

Rapid action to save species after the fires

Monday, 31 August 2020 -

Prioritising action for animal species after the fires

Tuesday, 01 September 2020 -

The little things count too: Prioritising recovery efforts for fire-affected invertebrates

Tuesday, 01 September 2020 -

Protecting persistence: Listing species after the fires

Tuesday, 01 September 2020 -

Fire and post-fire impacts on wildlife groups, and priority conservation responses

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

Post-fire recovery of Australia’s threatened woodlands: Avoiding uncharted trajectories

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

A conservation response to the 2019-20 wildfires

Tuesday, 21 January 2020 -

Considering cats and foxes after the bushfires: Fewer pests but more impact?

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

Threatened Species Recovery Hub statement on the fires

Tuesday, 14 January 2020