Moving mountains for the antechinus: The importance of food availability and high-elevation habitat

Wednesday, 21 October 2020Queensland has several species of antechinus, tiny insect-eating mammals. A few species need cool, moist, habitat found at high elevation. But as climate change advances, these rare and often threatened species are forced into ever smaller and higher areas on mountain-tops. Rachael Collett’s University of Queensland research shows that, without concerted action, the already-fragmented ranges of these cloud forest antechinus species may disappear to nothing. She takes up this story of ancient species with specialist habits.

Antechinuses are insectivorous marsupials found mainly on Australia’s east coast. The mountain ranges of eastern Queensland have the greatest diversity of antechinus species, with nine found between the New South Wales border and Cape York, weighing between 15g and 75g. They are agile and nocturnal, and insectivorous – they hunt arthropods (insects and spiders) in moist leaf litter and on tree bark at night.

Male antechinuses go out with a bang. At 11.5 months old, during their first (and only) breeding season, they become active day and night while searching for females and mating repeatedly for up to 14 hours at a time. This frantic mating period is over after two to three weeks in winter or early spring, and all males die soon after. Females usually survive until after their litter of eight young are weaned the next summer.

Springbrook National Park, Queensland, provides cool, moist habitat for the black-tailed dusky antechinus (Antechinus arktos). Image: Leanne White, DES

Springbrook National Park, Queensland, provides cool, moist habitat for the black-tailed dusky antechinus (Antechinus arktos). Image: Leanne White, DES

Cool climes, small ranges

Since 2012, three new species of antechinus have been discovered in Queensland. In 2018, two of these new species, the silver-headed antechinus (Antechinus argentus) and the black-tailed dusky antechinus (Antechinus arktos), were federally listed as Endangered. Both occur on isolated mountain-tops and are among the most geographically limited mammals in Australia.

Based on historical records from the 1970s and 80s and more recent survey efforts, the black-tailed dusky antechinus appears to have retreated to high elevations on the Tweed Volcano caldera. Similarly, the silver-headed antechinus is now only found at three small sites in central Queensland: the peak of Kroombit Tops near Gladstone, and the highest sections of Bulburin National Park near Miriam Vale and of Blackdown National Park near Emerald.

The poorly known Atherton antechinus (A. godmani) from Queensland’s wet tropics only occurs in a 30 km–wide band of rainforest above 650 m elevation in the Atherton uplands. The distribution and habitat of the Atherton antechinus is highly fragmented, and it is expected to lose much of its current range to climate change over the next 30 years.

The persistence of Australian insectivorous marsupials is thought to be tightly linked to the availability of their prey. Climate change has been implicated in reduced insect abundance in the northern hemisphere. Understanding the relationship between these insectivorous marsupials and their prey has become particularly important, as local populations of antechinuses disappear in drought, and they appear to be declining across Australia.

To understand why threatened antechinuses are so rare, and how climate change is affecting them, we collaborated with Andrew Baker at Queensland University of Technology and members of his mammal ecology lab, PhD students Eugene Mason, Emma Gray and Thomas Mutton, to examine antechinus population density across mountains in Queensland. We then looked at how population density was related to rainfall and seasonal food abundance.

Antechinus argentus female with 6–8 week-old pouch young. Image: Andrew Baker

Antechinus argentus female with 6–8 week-old pouch young. Image: Andrew Baker

Ancient species, modern problems

Historical data, combined with intensive live trapping and prey sampling has shown that the lowest population densities for antechinuses are in the tropics and at low elevations. Low population density is caused by limited food in winter, due to lower winter rainfall. High-elevation sites maintain high food abundance throughout the year because they receive ongoing “orographic” rainfall. This is rainfall produced as moist air lifts over a mountain range. Australian mountain-tops are therefore vital refuges for threatened and range-restricted antechinuses. As the climate continues to become hotter and drier, suitable climate for cool-adapted species is contracting to higher elevations, and year-round supply of the insects and spiders that these predators rely on is contracting along with it.

Winter (dry season) food is limited in the tropics. The rarity of tropical species has been noticed by past researchers, but the cause has remained elusive. We have shown that the low abundance of insects and spiders in winter helps to explain the rarity of antechinus species in the seasonal subtropics and tropics, including the Endangered silver-headed antechinus in central Queensland, and the restricted Atherton antechinus and rusty antechinus in far north Queensland.

Genetic research has established that Queensland antechinus species have been evolving for at least six million years, and the most recent species separated from sister species around 1 million years ago.

We also found that while up to three antechinus species could occur on the same mountain, they would have different elevational distributions. The most ancient antechinus species had the smallest ranges and only occurred on mountain-tops. This may be because they are restricted to cool climates and rainforest habitats most similar to those in which they evolved. These ancient antechinus species restricted to high elevations are at greatest risk from climate change. As the area of suitable climate, habitat and food decreases on mountain-tops, and antechinus distribution shrinks upwards, these rare and threatened animals may eventually have nowhere left to find refuge.

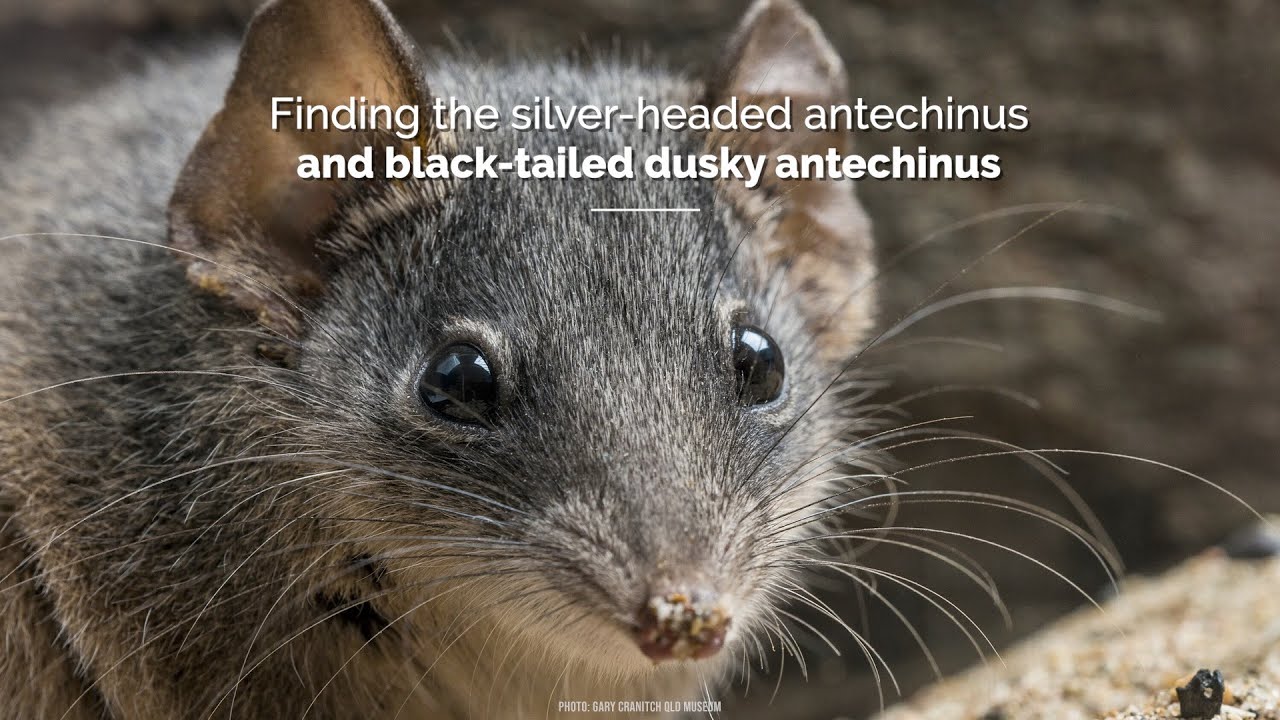

The black-tailed dusky antechinus (Antechinus arktos) has retreated to high elevations on the Tweed Volcano caldera. Image: Gary Cranitch, Qld Museum.

The black-tailed dusky antechinus (Antechinus arktos) has retreated to high elevations on the Tweed Volcano caldera. Image: Gary Cranitch, Qld Museum.

The threat of climate change

A substantial proportion of the world’s vertebrate fauna is insectivorous, and the prey base for these animals appears to be declining globally. Their cryptic and uncharismatic nature means that this loss of invertebrate biodiversity has received relatively little attention.

Our study has shown that the abundance of invertebrates can affect the persistence of threatened mammals that depend on them for food. Maintaining insect abundance should be a high conservation priority, not only because these species are important in their own right, but also because declines are likely to have detrimental flow-on effects on other species that depend on them worldwide.

We conclude that climate change is, and will continue to be, a major threat to the persistence of antechinuses. With changed climatic conditions, insectivorous species will need protected areas with high food abundance. Our study found that many Australian mountain-tops maintain high insect numbers year-round because they receive moisture from cloud-drip and orographic rainfall.

Most montane, high-elevation habitats where antechinus species occur have acted as refugia during past climatic changes, and they are likely to be important refuge areas under scenarios of ongoing climate change. Protecting these habitats is a critical priority. Luckily, many of these areas are currently located in national parks, but montane habitats outside of the reserve system should also be identified and preserved if we are to have the greatest chance of conserving these rare and ancient species.

Further information

Rachael Collett - rachael.collett@uqconnect.edu.au

Diana Fisher - d.fisher@uq.edu.au

Top image: Discovered in 2012, the silver-headed antechinus (Antechinus argentus) was federally listed as Endangered in 2018

-

Detection dogs rapidly filling the gaps for rare antechinus species

Tuesday, 26 November 2019 -

Finding the places where threatened species hide

Friday, 06 May 2016 -

Invasive species and habitat loss our biggest biodiversity threats

Monday, 10 December 2018 -

Life of quolls in the Pilbara

Tuesday, 04 December 2018 -

Mapping refuges across Australia

Tuesday, 05 July 2016 -

Rabbit burrows helping cats colonise new frontiers

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

The what, where and how of refuges for threatened animals - Ecological Society of Australia Refuges symposium

Tuesday, 29 May 2018