Tracking the far eastern curlew - News from Darwin and beyond

Tuesday, 29 May 2018The Hub’s far eastern curlew project team has tagged a bird travelling as far as North Korea this year. Along with other recent discoveries, the Darwin-based project is succeeding in its aim of closing significant knowledge gaps in the breeding habits and migratory movement of the bird. Amanda Lilleyman provides an update on their latest research findings and activities.

The far eastern curlew is in rapid decline in Australia – listed as Least Concern in 2004, it was upgraded to Endangered in 2015 and Critically Endangered in 2016. But while concerted effort is being made in Australia to conserve the species, we will not succeed unless we also consider the threats facing the bird along other parts of its migration route.

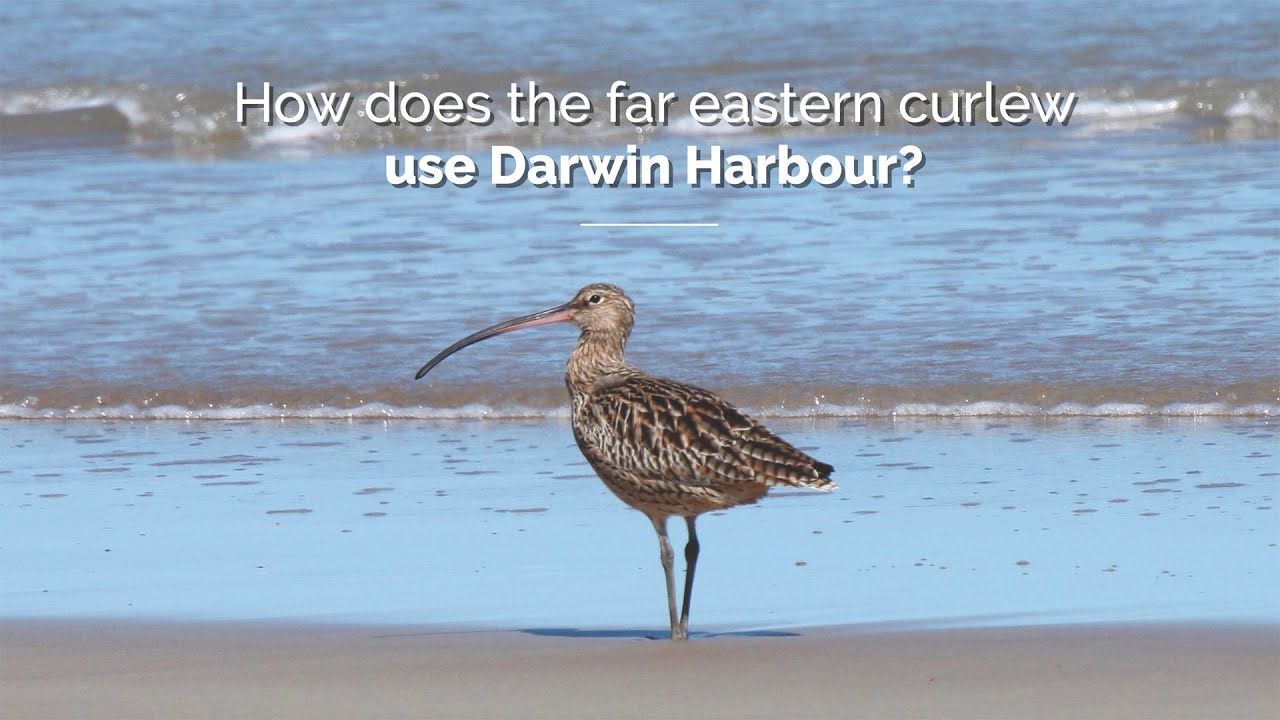

The exceptionally long-beaked bird is the world’s largest migratory shorebird. It travels 9,000 to 12,000 km each way along the ‘East Asian–Australasian Flyway’, between breeding grounds in Russia and China and non-breeding habitats in south-east Asia, Australia and New Zealand. Hub researchers focusing on one of Australia’s largest populations, which is found in Darwin Harbour, want to discover exactly where their birds go to breed as well as the migration path they take.

They also want to better understand their local movements within Darwin Harbour as this will provide valuable information about the birds’ preferred habitats and how and when they use them. This will include the most important feeding and roosting areas, and how these vary with tides.

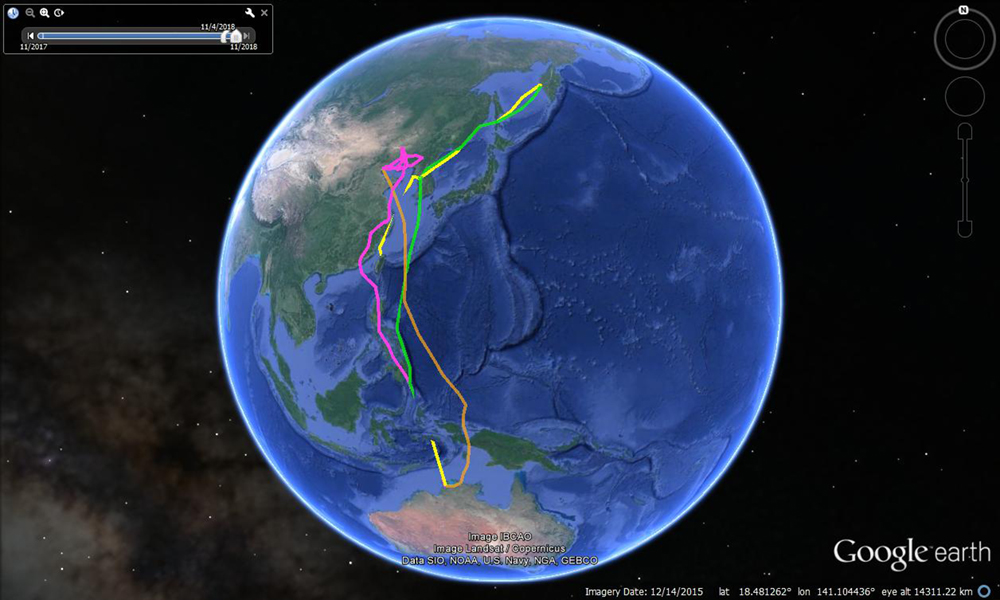

GPS tags have revealed the migratory routes of two far eastern curlew that left Darwin Harbour to travel to Northern Hemisphere breeding areas. One stopped in China to refuel mid-route, the other in South Korea. Image: CDU

Capture and tagging

Researchers caught two far eastern curlew in December 2017 and fitted GPS tags to them so they could track their movements around Darwin Harbour. The birds also have coloured flags with number codes attached to their legs so they are individually recognisable in the field. The two birds were coded ‘00’ and ‘01’, respectively.

It was quickly discovered that the birds were roosting at Darwin Port’s East Arm Wharf during high tide and using very small areas within Darwin Harbour for feeding during lower tides. Curlew 00’s tag switched off within a month of tracking as its solar panel was obstructed by wing feathers and prevented from recharging, staying off for several months. But Curlew 01 gave the researchers five months of fine-scale tracking from Darwin Harbour.

This bird would often roost in the dredge ponds at East Arm Wharf, and move between there and two saltpans nearby and four kilometres away in Charles Darwin National Park. This extensive use of saltpans was unexpected. The bird also used the mudflats out the front of the mangroves of this area, at low tide. It used these four sites exclusively over the five months of tracking and was often resighted at East Arm Wharf during high tide.

A far eastern curlew being fitted with a GPS tag to track movements around Darwin Harbour and along its migration route. Photo: Gavin O'Brien

Northern flight

Curlew 00’s tag switched on again on 4 April 2018, where it was logged on the coast between Taiwan and Fujian. The next day it arrived on the coast of North Korea, where it stayed for four days, before flying over the border to South Korea. It spent its time feeding on the mudflats near Incheon. It has since moved on to breeding grounds on the Kamchatka Peninsula in far East Russia.

Curlew 01 started its northward migration on 25 April. The researchers tracked it flying over the Philippines, then arriving on the coast between Hong Kong and Fujian before flying further north to Hangzhou Bay in China (which is the far southern part of the Yellow Sea). The late April departure date is very late for the species – curlew usually depart north in late February and early March. The team were expecting this bird to stay in Darwin as it was sub-adult, and were surprised to see it start migration and reach so far north so quickly.

All eyes will be on whether it travels to the northern hemisphere breeding grounds.

Far eastern curlew make epic cross-globe migrations between breeding and non-breeding areas. Photo: Amanda Lilleyman

For further information

Amanda Lilleyman - amanda.lilleyman@cdu.edu.au

Top image: Inspecting wing moult on a far eastern curlew. Photo: Gavin O'Brien

New Chinese policy a big win for Australia’s curlew

The shorelines that many coastal shorebirds rely on have changed dramatically over the last several decades. Land reclamation has transformed much of the natural coastline of the Yellow Sea into hardened seawalls, inside which intertidal flats have been converted into hard land for ports, aquaculture and industrial zones.

Seven threatened Australian shorebird species pass through China on migration. Loss of tidal flats, including through land reclamation, has driven steep population declines across many species, including those listed as threatened in Australia. But a recent announcement from the Chinese government is a hugely positive development for shorebirds and their coastal habitats.

China’s State Oceanic Administration stated in early 2018 that henceforth the agency will only approve coastal wetland development that is important for public welfare or national defence (rather than for business-related reasons), that unauthorized reclamation projects will be stopped, damaging structures on illegal reclamation areas torn down, and already-reclaimed wetlands that have not yet been built will be nationalised.

Sea walls and land reclamation have greatly reduced the extent of mud flat habitats in China. Photo: Micha Jackson

If systematically implemented, this new policy could greatly reduce one of the largest pressures on intertidal shorebird habitat (development-related reclamation), and allow for increased focus on the maintenance and improvement of existing intertidal and supratidal habitat to foster shorebird recovery.

Intertidal flats are also threatened by the invasion of Spartina cordgrass, pollution and coastal erosion, requiring concerted management efforts, while less developed supratidal areas have enormous potential to improve available coastal shorebird habitat if strategically managed to benefit bird species.

For further information

Micha Jackson - m.jackson@uq.net.au