Unique yet neglected: The Australian snakes and lizards on a path to extinction

Tuesday, 10 November 2020Many Australian reptile species are in trouble. Without a stepping up of conservation action Australia’s extinction rate is set to increase in coming decades. Hayley Geyle from Charles Darwin University and Associate Professor David Chapple from Monash University have been working with reptile experts from across the country to identify the species at greatest risk of extinction in order to provide time to act before it is too late.

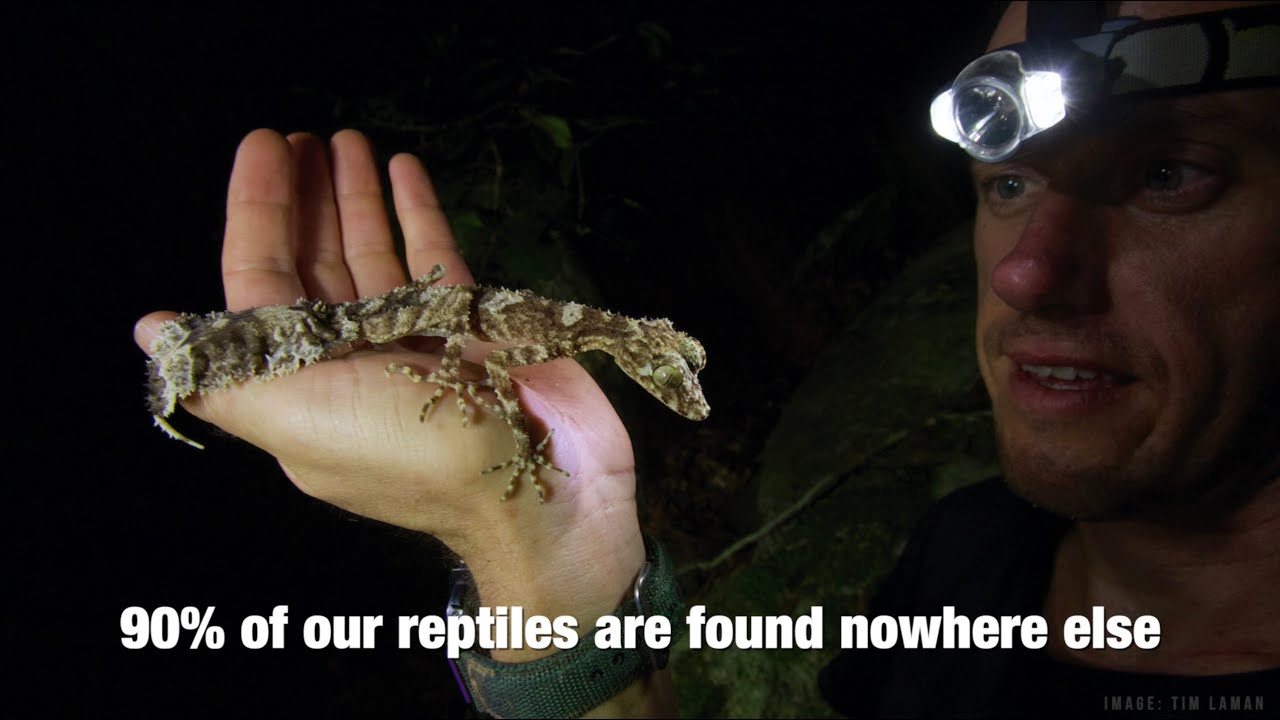

Australia is a hotspot for reptile diversity; we have the largest number of species of any country in the world, and about 10% of all known species globally. From tiny skinks to charismatic dragons, our reptile fauna are very distinctive. More than 90% of our species occur nowhere else in the world, but many of these uniquely Australian fauna are at risk of extinction.

Reptiles are undergoing widespread declines on a global scale, which is likely to be further exacerbated by climate change. There has been little conservation action for most Australian species at risk, partly because reptiles are poorly known. New species are being described at an average rate of 15 per year, many of which are already vulnerable to extinction at the time of discovery.

The Cape Melville leaf-tailed gecko, pictured here with researcher Conrad Hoskin, is restricted to the top of a small mountain range on Cape York and is threatened by climate change. Image: Tim Laman

The Cape Melville leaf-tailed gecko, pictured here with researcher Conrad Hoskin, is restricted to the top of a small mountain range on Cape York and is threatened by climate change. Image: Tim Laman

This lack of action has also been compounded by few reptiles in Australia being well monitored. Without adequate monitoring, we have a poor understanding of population trends and the impacts of threats, meaning that species could slip into extinction unnoticed.

Reptiles also lack the public and political profile that helps generate recovery support for other Australian threatened animals (such as the arguably more charismatic mammals, birds or frogs), leading to little resourcing for conservation.

Only one Australian reptile is officially listed as extinct, but we have most probably lost others before knowing of their existence. In the wake of continued decline and increasing pressures associated with ongoing threatening processes, we will only prevent extinction by recognising risks in time to do something about them.

The approximate locations of the 20 terrestrial snakes and lizards at greatest risk of extinction.

Six species more likely than not to go extinct by 2040

Our research team – including 27 reptile experts from universities, zoos, museums and government organisations across the country – identified the terrestrial snakes and lizards (collectively known as squamates) at greatest risk of extinction within the next two decades, assuming no changes to current management. The study has been published in Pacific Conservation Biology.

Our research predicts that up to 11 species could be lost within 20 years unless there is a stepping up of conservation action. This would represent a marked increase in the extinction rate for Australian reptiles relative to historic levels. The species in greatest peril include two dragons, one blind snake and three skinks, but many others could also be lost.

A recent assessment found that all 20 species at greatest risk meet internationally recognised criteria for listing as threatened (IUCN Red List), but only half are currently protected under Australian environmental legislation. This suggests that the EPBC Act list of threatened species needs urgent review.

LEFT: The Arnhem Land gorges skink is one of six species considered more likely than not to become extinct within the next two decades. Threats to this species include changes to food resources and habitat quality caused by altered fire regimes, feral cats and, possibly, poisoning by cane toads. Image: Chris Jolly; RIGHT: The Mount Surprise slider is threatened by multiple invasive plant species and compaction of sandy soils by cattle. Image: Stephen Zozaya

Queensland species especially vulnerable

More than half (55%) of the 20 species at greatest risk occur in Queensland. Three are known from islands: two on Christmas Island, and one on Lancelin Island – a tiny low-lying sand island off the coast of Western Australia. Two more species are found in Western Australia, while the Northern Territory, the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and New South Wales each have one species.

Each of the 20 species occurs in a relatively small area, which probably explains the Queensland cluster – many species in that state naturally have very small distributions. Most of the 20 at greatest risk occupy 16 km2 or less, so could be lost to a single catastrophic event, such as a large bushfire.

LEFT: The tiny Lancelin Island ctenotus is found only on Lancelin Island, 100 km north of Perth. Its threats include habitat changes caused by weeds, declining shrubs and human disturbance. Image: Brad Maryan; RIGHT: The Endangered Christmas Island forest gecko is threatened by Asian wolf snakes, giant centipedes and rats, which have been introduced to Christmas Island. Image: Jon-Paul Emery

LEFT: The tiny Lancelin Island ctenotus is found only on Lancelin Island, 100 km north of Perth. Its threats include habitat changes caused by weeds, declining shrubs and human disturbance. Image: Brad Maryan; RIGHT: The Endangered Christmas Island forest gecko is threatened by Asian wolf snakes, giant centipedes and rats, which have been introduced to Christmas Island. Image: Jon-Paul Emery

The threats facing our terrestrial snakes and lizards

Invasive species were the most common threat, including weeds (and their interaction with fire), feral cats, red foxes, black rats, pigs, deer, horses, introduced invertebrates, oriental wolf snakes and cane toads (through predation, poisoning or direct habitat destruction). Habitat loss or modification (through agriculture, urbanisation, altered fire regimes and mining) and climate change were also important threats.

Many threatened reptiles are associated with habitats that historically have been, and still are being, rapidly transformed into farmland, such as the temperate grasslands of south-eastern Australia and the brigalow woodlands of central Queensland. For many of the species currently persisting in highly modified landscapes, changing land use is ongoing, and highly likely to be contributing to further declines.

For example, a shift from mixed-crop farms to broadacre monocultures (often irrigated cotton) in the Condamine River floodplains has led to the destruction of critical habitat for the Condamine earless dragon.

LEFT: The Lake Disappointment ground gecko is known only from a single location, greatly increasing the risk that a single event could cause its extinction. Image: Brad Maryan; RIGHT:The large and prickly Pinnacles leaf-tailed gecko is only found in the Pinnacles range near Townsville, where the population is estimated to number only 250. Wildfire, invasive species and poaching are all significant threats to this rare species. Image: Stephen Zozaya

LEFT: The Lake Disappointment ground gecko is known only from a single location, greatly increasing the risk that a single event could cause its extinction. Image: Brad Maryan; RIGHT:The large and prickly Pinnacles leaf-tailed gecko is only found in the Pinnacles range near Townsville, where the population is estimated to number only 250. Wildfire, invasive species and poaching are all significant threats to this rare species. Image: Stephen Zozaya

Lessons from the past

Despite early warnings of significant declines, the Christmas Island forest skink holds the unenviable title of the first Australian reptile to be officially listed as extinct. Action came too late for this species; it was lost from the wild before it was listed as threatened, and the few individuals brought into captivity died soon after it was listed as Critically Endangered under Australian environmental legislation.

Without increased resourcing and management intervention, many more Australian reptiles could follow the same trajectory as the Christmas Island forest skink.

But it’s not all bad news – the pygmy bluetongue skink was once thought to be extinct, until a chance discovery kickstarted a long conservation and research program. Translocations are now being undertaken to establish new populations, signifying that positive outcomes are possible when informed by good science.

By identifying the species at greatest risk, we hope to forewarn governments, conservation groups and the community, giving them time to act to prevent further extinctions before it is too late.

Further information

Hayley Geyle - hayley.geyle@cdu.edu.au

David Chapple - david.chapple@monash.edu

Work cited:

Geyle, H.M., Tingley, R., Amey, A.P., Cogger, H., Couper, P.J., Cowan, M., Craig, M.D., Doughty, P., Driscoll, D.A., Ellis, R.J., Emery, J-P., Fenner, A., Gardner, M.G., Garnett, S.T., Gillespie, G.R., Greenlees, M.J., Hoskin, C.J., Keogh, J.S., Lloyd, R., Melville, J., McDonald, P., Michael, D.R., Mitchell, N.J., Sanderson, C. Shea, G.M., Sumner, J., Wapstra, E., Woinarski, J.C.Z., and Chapple D. (2020). Reptiles on the brink: identifying the Australian terrestrial snake and lizard species most at risk

of extinction. Pacific Conservation Biology. https://doi.org/10.1071/PC20033

Top image: Habitat loss and degradation due to agriculture is a major threat to the Roma earless dragon. Although assessed as Endangered under the IUCN Red List, it has not been listed under Australian legislation. Image: A. O’Grady Museums Victoria

-

The Australian freshwater fishes at greatest risk of extinction

Tuesday, 01 September 2020 -

Preventing extinctions of Australian lizards and snakes

Tuesday, 02 February 2021 -

Saving Tasmania's difficult birds

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Please save these frogs: The 26 Australian species at greatest risk of extinction

Friday, 20 August 2021

-

Big trouble for little fish: The 22 freshwater fishes at risk of extinction

Wednesday, 21 October 2020 -

A review of listed extinctions in Australia

Tuesday, 12 November 2019 -

No surprises, no regrets: Identifying Australia's most imperilled animal species

Monday, 24 September 2018 -

Tasmanian birds top endangered species list

Thursday, 07 July 2016 -

2020 target set for more threatened species

Monday, 28 March 2016 -

Keeping up with biodiversity loss

Thursday, 26 November 2015 -

Reflections on loss

Thursday, 09 June 2016 -

Researcher Profile: Hayley Geyle

Wednesday, 28 October 2020 -

Aussie icons at risk: Scientists name 20 snakes and lizards on path to extinction

Tuesday, 29 September 2020 -

22 Australian freshwater fish at risk of extinction

Tuesday, 29 September 2020 -

‘Australian Fritillary’ and ‘Pale Imperial Hairstreak’ top list of butterflies at risk of extinction

Tuesday, 27 April 2021 -

These frogs need our help: Scientists name the Australian frogs at greatest risk of extinction, four likely already lost

Friday, 20 August 2021