Appeasing Bluetongue Managing fire in the Great Sandy Desert

Tuesday, 13 August 2019Karajarri Rangers are leading a Threatened Species Recovery Hub research project to investigate how different fire management approaches affect biodiversity. The first field trip took place in April this year, when a team of 16 rangers, support staff and scientists journeyed to the Edgar Ranges for eight days of wildlife monitoring. Hub researcher Sarah Legge worked with the rangers to compile this report from the field.

The Karajarri Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) covers 2.4 million hectares in north-west Australia, south of Broome. It is bounded to the west by 80 Mile Beach, seasonal home to spectacular aggregations of migratory shorebirds. Travelling inland, the coastal pindan woodlands grade slowly into the‘pirra’ (shrublands) and ‘marangurru’(spinifex country) of the Great Sandy Desert, home to threatened and culturally important species including bilbies, emus, bush turkeys and goannas.

Although the IPA is largely desert, most Karajarri people live on the coast at Bidyadanga. The Karrajarri Rangers initially worked in coastal habitats, but they are extending their program into the pirra and marangurru. This management focus is an opportunity to reinvigorate the stories, cultural practices and connections between people and desert Country. Managing fire is a key component of this program.

Sam Bayley, the IPA coordinator, notes, “There has been good work demonstrating the social benefits of investing in ranger programs. We want to also document the biodiversity benefits, including of our fire management.”

Beno and Marissa set up a drift fence. Image: Sarah Legge

Where are we going?

After leaving Broome and crossing the Roebuck plains, our convoy travelled south-east along station tracks and disused mining exploration tracks, eventually reaching the Edgar Ranges. Gulu, the head ranger, selected the campsite on the desert sandplain near the edge of a scarp that falls away sharply to form the headwaters of the north-flowing Geegully drainage. Gulu and Jacko, senior rangers with family connections to this area, formally introduced the team to their Country, smoking us with jima (conkerberry) wood.

Why are we here?

Mervyn Mulardy, a Karajarri cultural leader, gave us the Pukarri (Dreaming) story for the area (Yilpi). The Pukarri highlights the potential for huge desert wildfires: “Bluetongue was told that his son will be going through the sacred ceremony, so he said to the tribe, ‘Wait, I will get more food’. So he went hunting. When he came back he saw that they had already put his son through the ceremony without him being there. Bluetongue was really angry, so he started a fire at this Yilpi. He made a huge fire that burnt the whole country, burning the people who had disrespected him.”

When Karajarri still lived in the pirra and maranguru, they used fire intensively for many purposes, creating fine-scale patchworks of different-aged vegetation, which discouraged large fires. As people moved out of the deserts, fuel loads became more continuous, and sweeping fires that burn extensive areas of country became common. This new fire pattern has contributed to biodiversity losses in these remote deserts. Jacko told us, “My grandmother used to travel through here. She’s really old. She told us lots of stories from these places, and she can remember animals that are gone now.”

Managing fire across vast areas of depopulated deserts is a logistical challenge, which Karajarri are solving by adopting the aerial burning approaches used extensively further north, in the tropical savannas.

Bayo: “In this desert Country, my grandfather’s Country, we have lots of story places, but it’s been hard to get to these areas in the last years to look after things. Now, with helicopters for fire management we can reach places we can’t get to with the vehicle. We’ve been opening up jilas [waterholes] that haven’t been looked after for 60 to 70 years.

“I went to Botswana this year, representing the rangers, talking about our fire work – how we carry it out, and how we know if it is doing a good job. That’s where this monitoring program comes in – it will help us know if our fire management is succeeding.”

Sheen: “We are doing this work to see what animals are here, check out if the country is in good shape, and if the fire management is working.”

LEFT: Sheen with a northern shovel-nosed snake; CENTRE: Bayo checks a funnel trap; RIGHT: Kamahl with a desert rainbow skink. Images: Sarah Legge

What are we doing?

Tracking change in the deserts as a result of fire management will take years. We can learn some things more quickly by comparing the vegetation and wildlife at sites that were recently burnt in a monster 2018 wildfire with sites in areas that escaped that fire due to sudden wind changes. We’re also going to trial some standardised searches for bush tucker, and we have some bilby burrows to check on.

Setting up

We spend the first two days setting up the sampling sites, digging in 800 metres of drift fences to direct small animals towards 80 pitfall traps, 32 funnel traps and 32 camera traps. It’s hot (40°C in the shade) and the humidity ranges between 50 and 90%. By midday on day 2, we are shovelling dirt in a slow, headachy trance. Ewan and Jackie, the coordinators for the men and women rangers respectively, keep us toiling in good spirits with their buoyant humour and excellent organisation.

Sheen, Moonie, Gulu and Ewan enter data back at camp. Image: Sarah Legge

Checking traps

The first morning we check traps, we are rewarded with a lovely range of small reptiles and clusters of frogs. Marissa, the newest recruit to the women rangers, says that her favourite animal is “these little toads, I’ve never seen them before”. She’s carefully giving each desert spadefoot toad and every west Kimberley toadlet its own fresh water spa before releasing them into a burrow that Sheen has dug and moistened.

Kamahl votes: “I like this desert rainbow skink.” Bayo wants an emu (although they generally don’t fit into pitfall buckets). “Nice choices”, I think to myself. At that point, the sighting of a mulga snake sends most of us hurtling back to the car.

Scrabbling around at the bottom of a bucket, Jess evades scorpions to fish out a western two-toed slider. Jess and Nigel are Environs Kimberley ecologists who are here to support the rangers. Sheen coaxes Marissa to hold the slider. It’s a skink, but with no forelimbs, tiny back limbs and a powerful wiggle, its slippery pinkish body is too reminiscent of a snake for her liking. Sheen: “These are amazing little animals; they can burrow through the sand really fast. They can also drop their tails if a predator catches them, to get away.” Jacko and Gulu tell us that “the old people used to put sliders in their hair, to eat head lice”. We discuss how I could smuggle some home to deal with the lice my daughter regularly brings back from school, but the logistics of containing these slippery little beasts on the head defeat us.

Jackie and Ewan start checking the camera trap SD cards mid-survey. The camera traps have picked up native mice climbing over the drift fence. That’s okay, we knew they would, and that’s why we set the cameras up. But Jackie also hoots at a prowling tabby cat onscreen. By the end of the week we have seen cat tracks at every trapping site, and at one site a camera detects a fox. Foxes are rare in these northern deserts; perhaps he’ll head south again as the dry season wears on and water becomes scarce.

We wonder if cats and foxes are responsible for the emptiness of the bilby burrows that we check. The bilbies were here last year, before the huge wildfire, but they’re not at home now. Bayo reckons “bilbies like areas that are burnt two to five years ago”. Paddy: “This is why we need to get fire under control; we want to make sure those bilbies stick around.”

The week rolls by in an enjoyable daily routine that starts with pre-dawn campfire coffee as we watch the eastern sky turn orange and pink. The flies are watching the same sunrise, and we leave to check traps when their numbers become unbearable. After trap-checks, bird surveys and an obligatory second breakfast, some of the team stay at camp to enter data with Gary and Gareth, TAFE teachers who have accompanied the team to provide literacy and numeracy support. The rest of us head back out to do vegetation surveys, and to trial bush tucker searches.

Lesser hairy-footed dunnart. Image: Sarah Legge

Bush tucker searches

We decide to trial the bush tucker searches in vegetation of different post-fire ages “to see if there is good bush tucker in each spot” (Jacko). We start off well, finding food and medicine plants including jilarlgka (bush tomato), yukurli (dodder), wutarr (gardenia), jima (conkerberry), kumanu (sandalwood) and kurlulu (cornwood) in patches of vegetation that recently burnt. Jacko and Gulu tutor the group on language names and uses.

Our sampling design gets a reality check when Sheen, Jacko and I pull up next to a patch of wattle shrubland that last burnt many years ago – it is thick, impenetrable and unappealing. Sheen’s not keen. I look at Jacko; her face is shaded with apprehension. I ask, “Jacko, you reckon those old people would go in places like that for bush tucker?” Jacko, with relief: “No. They might burn it, come back later.”

We realise our sampling design for bush tucker might be scientifically sound but it’s asking the wrong question. We better go and think about this over a cuppa. The cuppa is an infusion of supplejack bark and native lemongrass that Gulu and Jacko have prepared because some of the team have come down with colds.

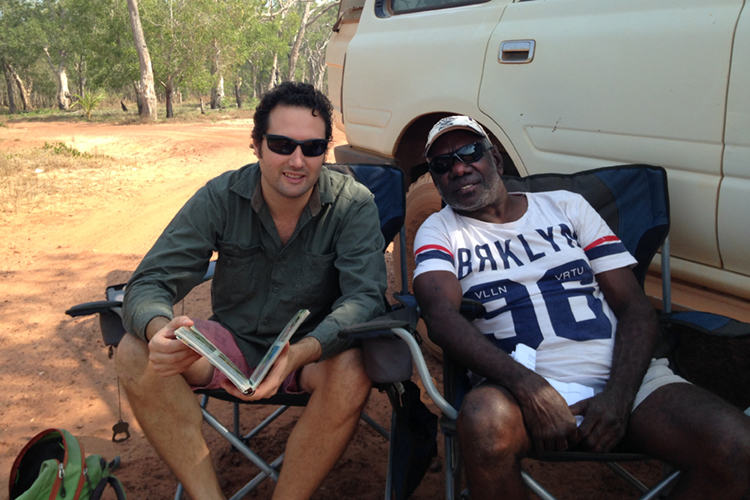

Jacko and Sarah doing a vegetation survey. Image: Sarah Legge

What’s next?

Over the week, we catch 750 animals from 35 reptile species, four frog species, and 13 mammal species (including seven bats). Our bird surveys count 1907 birds from 38 species, with another 19 species recorded incidentally.

We are already starting to notice some patterns. For example, delicate mice seem more common at recently burnt sites, but lesser hairy-footed dunnarts and sandy inland mice only popped up at long-unburnt sites. Diurnal, surface-dwelling skinks (e.g. Ctentous spp.) are rarer on recently burnt sites, but the sliders, which spend most of their time underground, turn up across sites regardless of fire history. Some interesting analyses beckon! We want to figure out which species, from bilbies to skinks, might be declining because of wildfire, and make sure the fire management looks after them.

Although we’ve done only our first fieldtrip, Sheen and Beno already reckon that “the data we’ve collected will help us understand how animals are affected by fire, and that will help us manage fire”. Bayo: “We can see that bilbies don’t like those big, hot fires, but there are more emus around than we thought, and quite a few turkeys.” Paddy: “There are too many cats here, and foxes too now.”

Our next fieldtrip, to a different part of the desert (Kalkarra), is planned for October. We’ll have a similar monitoring method, and with that extra data, we’ll be able to tell more about how fire affects different species. We’ll also have a solid baseline to allow Karajarri to track changes over time.

Last, but most deeply, by being here together and sharing our knowledge, by reaching back in time through stories that senior rangers heard from their grandparents, we begin to connect with each other, and the story for this country.

This project receives support from the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub.

This project is a collaboration between Karajarri Traditional Lands Association, Kimberley Land Council, the Threatened Species Recovery Hub and Environs Kimberley, with additional support from The Nature Conservancy, Bush Heritage Australia, Western Australian Government’s State NRM Program and the Western Australia Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions

For further information

Sarah Legge - sarahmarialegge@gmail.com

Top image: The Edgar Ranges Field Crew included Karajarri Rangers, Environs Kimberley, TAFE and the Threatened Species Recovery Hub. Image: Gary Lienert

-

Cultural fire: Listening to and caring for Country with fire

Monday, 31 August 2020 -

Pirra Jungku (desert fire): New ways for traditional burning

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

Indigenous advisor profile: Oliver Costello - Healing Country with cultural fire

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

Indigenous Engagement Protocols: Forging respectful, meaningful partnerships for research impact

Wednesday, 21 October 2020 -

Changing the way research is driven

Tuesday, 13 August 2019 -

Indigenous engagement vital to saving species

Tuesday, 29 May 2018 -

Indigenous land manager profile: Braedan Taylor

Tuesday, 30 June 2020 -

Indigenous people critical for threatened species

Tuesday, 13 August 2019 -

Looking after culturally significant and threatened species on the Tiwi Islands

Tuesday, 20 August 2019 -

Partnerships with Indigenous communities key for threatened species

Wednesday, 30 March 2016 -

What's the overlap

Wednesday, 07 June 2017 -

Working together to care for the Byron Bay orchid

Tuesday, 20 August 2019 -

Building collaboration and two-way science

Sunday, 12 December 2021