Building collaboration and two-way science

Sunday, 12 December 2021 Professor Sarah Legge,

Professor Sarah Legge,

The University of Queensland/The Australian National University

Threatened Species Recovery Hub

Deputy Director

(Image: Katherine Tuft)

Let’s be honest – the process of getting large Commonwealth-funded research hubs off the ground isn’t suited to upfront consultation with Indigenous groups and communities. Once the main contract is signed, the first research plan needs to be developed very quickly, totally out of sync with the time needed to build the relationships and trust that are the foundation for co-developing a collaborative project with Indigenous partners.

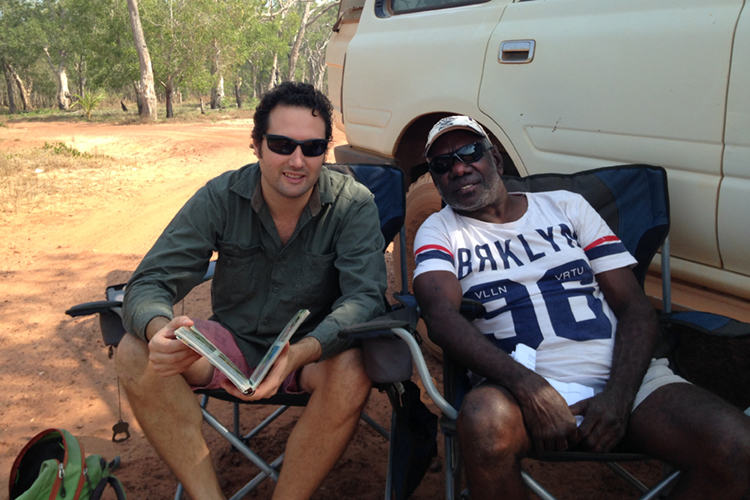

So, at the start of the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, we had to put steps in place to build the trajectory towards the engagement and communication we were aiming for. A key step was having Brad Moggridge join the team as the Indigenous Liaison Officer, to provide guidance to project teams. This guidance included developing a document with advice to early career researchers on how to develop respectful relationships with Indigenous people.

Brad was supported by the hub’s Indigenous Reference Group. This powerhouse advisory group (Cissy Gore-Birch, Stephen van Leeuwen, Oliver Costello, Teagan Goolmeer, Larissa Hale and Gerry Turpin) fostered Indigenous collaborations and communication with the hub, and led or participated in some nationally important work. For example, they led the national conversation on culturally significant species (how to define them, and how to get them recognised in environmental policy and law) that fed through several pathways into the recent EPBC Act review.

Through discussions with Brad and the Indigenous Reference Group, project leaders were encouraged to consider the relevance of their work to Indigenous people, and how best to involve them in that research. Over time, the dynamic shifted, and by the final couple of annual research plans, projects were being proposed that were initiated and co-led by ranger groups. For example, the Karajarri Rangers began a project in 2018 with scientific support from the hub to improve fire management for threatened species and other fauna in their Indigenous Protected Area; the project has since grown to include the Ngurrara Rangers, Karajarri’s neighbours in the Great Sandy Desert, and the two ranger groups have carried out joint surveys, sharing skills.

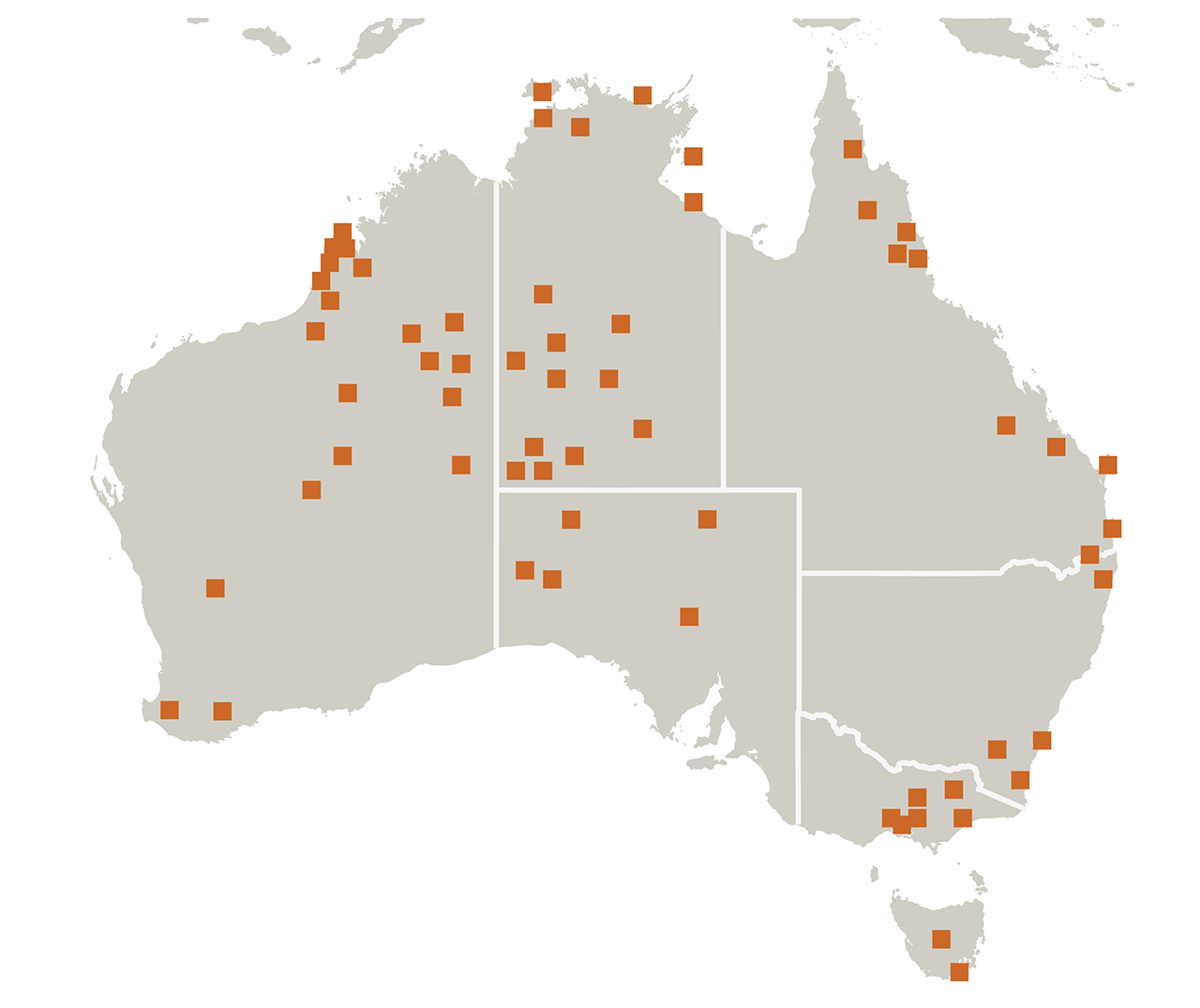

The locations of Indigenous groups that the hub engaged with.

The locations of Indigenous groups that the hub engaged with.

By the end of the hub’s six-year program we had supported a diverse and productive range of research with Indigenous partners. For example, 65 Indigenous organisations had been engaged with hub research projects, and an average of 98 rangers per year worked alongside hub researchers in two-way knowledge exchange. Over 70 communication products have been produced with and for Indigenous audiences, including videos, factsheets, posters, media and animations.

Projects with substantial Indigenous engagement were scattered right across Australia, from Martu in the west to Arakwal in the east, and from Tiwi in the north to Wurundjeri in the south. The projects that were Indigenous-led, or had substantial engagement, had developed enough momentum to withstand the disruption that COVID-19 caused to travel, but it remains extremely disappointing that the on-country trips and gatherings of the first four years had to be replaced in the last 18 months by online meetings and emails.

I hope one of the legacies of the hub will be the relationships that developed through the research projects, and what these lead to. Maybe these relationships will even oil collaborations in future hubs, supporting Indigenous groups and people to get involved in the planning processes earlier, and to drive the research agenda.

Professor Sarah Legge

Top image: Tiwi Land Rangers setting up cage traps for fauna surveys as part of a hub collaboration with Charles Darwin University scientists which has looked at trends in small mammals and cat occurrence and how these are influenced by fire management. Image: Hugh Davies

-

Combating a conservation catastrophe: Understanding and managing cat impacts on wildlife

Tuesday, 06 October 2020 -

Species of the Desert Festival 2019

Friday, 27 March 2020 -

Protecting Tiwi mammals

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

How does fire affect Karajarri Country?

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Looking for night parrots

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Talking night parrots on Paruku Country

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Island Way, Desert Way - Kiwirrkurra and li-Anthawirriyarra Rangers share cat management knowledge

Tuesday, 12 October 2021

-

Cultural fire: Listening to and caring for Country with fire

Monday, 31 August 2020 -

Small mammal declines in the Top End - Causes and solutions

Monday, 31 August 2020 -

Managing fire to protect monsoon vine thickets on the Dampier Peninsula

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

Pirra Jungku (desert fire): New ways for traditional burning

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

Indigenous advisor profile: Oliver Costello - Healing Country with cultural fire

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

Indigenous Engagement Protocols: Forging respectful, meaningful partnerships for research impact

Wednesday, 21 October 2020 -

A Martu method for monitoring mankarr (greater bilby)

Tuesday, 20 August 2019 -

Appeasing Bluetongue Managing fire in the Great Sandy Desert

Tuesday, 13 August 2019 -

Changing the way research is driven

Tuesday, 13 August 2019 -

Connecting Victorian kids with Indigenous culture and the environment

Tuesday, 20 August 2019 -

Conserving Australia’s ghost of the arid interior – the night parrot

Tuesday, 26 September 2017 -

Designing a best-practice bilby monitoring program for Martu rangers

Thursday, 15 December 2016 -

Endangered bilby connects communities across time and space

Wednesday, 06 July 2016 -

Indigenous engagement vital to saving species

Tuesday, 29 May 2018 -

Indigenous land manager profile: Braedan Taylor

Tuesday, 30 June 2020 -

Indigenous land manager profile: Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa and Martu people

Tuesday, 30 June 2020 -

Indigenous people critical for threatened species

Tuesday, 13 August 2019 -

Looking after culturally significant and threatened species on the Tiwi Islands

Tuesday, 20 August 2019 -

Melville Island mammal declines fought with fire

Monday, 13 March 2017 -

Monitoring malleefowl on a massive scale

Monday, 08 August 2016 -

More data to tackle threats to Malleefowl

Thursday, 05 May 2016 -

Partnerships with Indigenous communities key for threatened species

Wednesday, 30 March 2016 -

Talking night parrots on Paruku Country

Tuesday, 12 March 2019 -

The fire, the fox and the feral cat

Tuesday, 06 June 2017 -

Tiwi Island mammals: Saving the brush-tailed rabbit-rat

Tuesday, 11 September 2018 -

Tracking cats to help the night parrot

Wednesday, 05 June 2019 -

Using fire to reduce cat impacts on the Tiwi Islands

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

What's the overlap

Wednesday, 07 June 2017 -

Working together to care for the Byron Bay orchid

Tuesday, 20 August 2019 -

Kids learning to track Mankarr on Martu Country

Wednesday, 28 October 2020 -

Cat science finalist for Eureka Prize

Monday, 28 September 2020