Beyond captivity for Christmas Island reptiles

Tuesday, 26 November 2019In 2009, the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink and Lister’s gecko were headed for imminent extinction. Parks Australia acted quickly to collect remaining wild individuals in order to establish captive breeding programs on Christmas Island and at Taronga Zoo, Sydney, which have been highly successful. A Threatened Species Recovery Hub project team is working closely with Parks Australia to help secure a future for the two lizards beyond captivity. Jessica Agius, Jon-Paul Emery and John Woinarski report on the latest developments and the challenge of protecting these ancient and unique island reptiles.

Many species occur only on islands, a characteristic that has long fascinated biologists. But while evolution in isolation has led to new species, it has also rendered these species highly vulnerable to changes in their environment, such as the arrival of new predators. In Australia, our three most recent extinctions have all been island endemics.

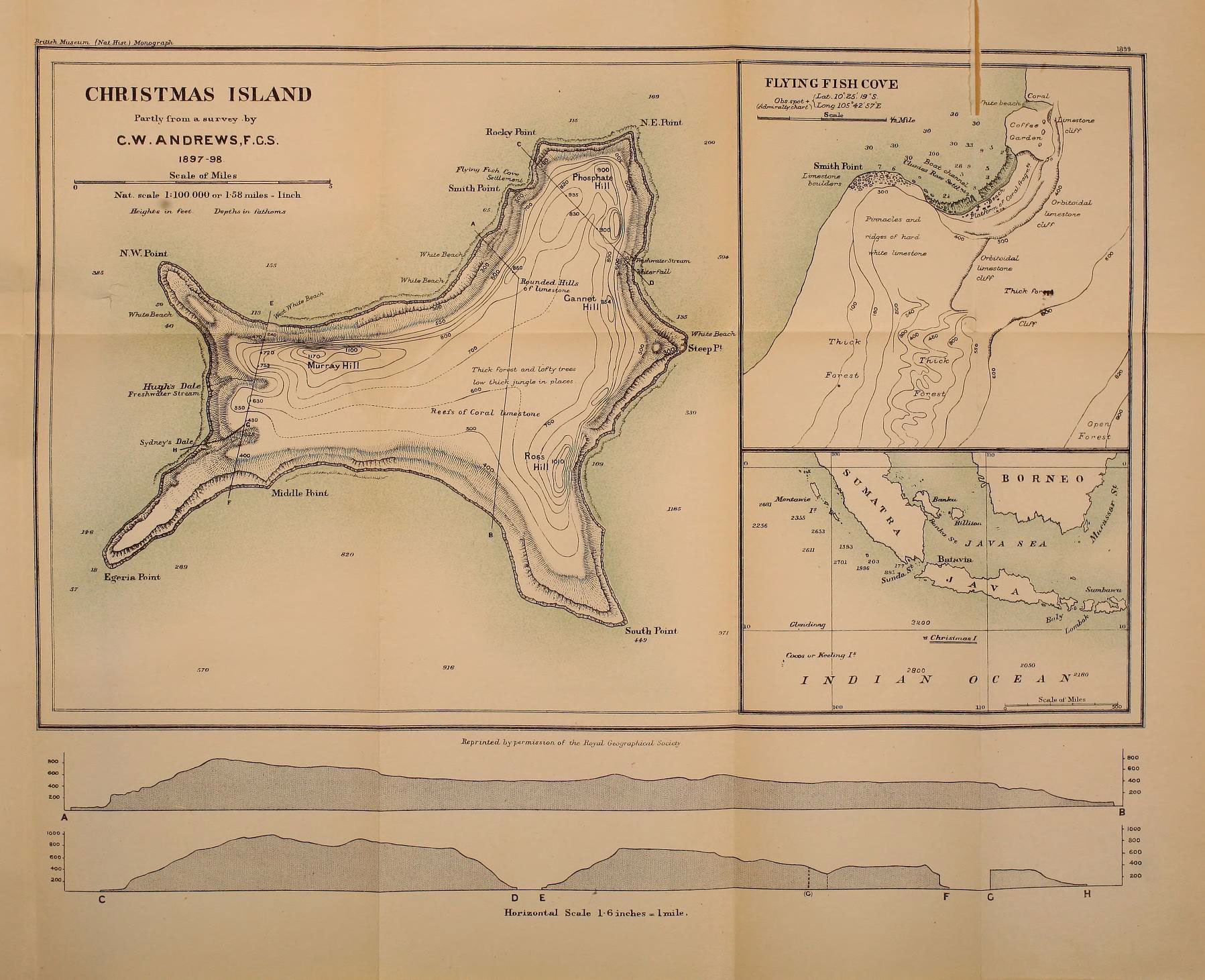

The Australian external territory of Christmas Island, which lies 1550 km off the north-western coast of mainland Australia, is a case in point. The island had an intriguing reptile fauna, comprising one endemic blind snake, two endemic geckos, two endemic skinks, and one native skink that also occurs elsewhere. These endemic species existed on the island for several million years, and all of the lizards remained common up to the 1970s, but four then declined precipitously. These declines now seem most likely to have been caused by the inadvertent introduction of the Asian wolf snake (Lycodon capucinus) from stowaways on freight shipping.

Observing the decline in wild populations, in 2009 and 2010 Parks Australia managed to secure enough individuals of the blue-tailed skink (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) and Lister’s gecko (Lepidodactylus listeri) to establish captive breeding populations. Shortly after, they became extinct in the wild. The opportunity came too late for the Christmas Island forest skink (now extinct) and coastal skink (now extirpated from Christmas Island). However, the captive populations of the blue-tailed skink and Lister’s gecko have flourished. The 66 skinks collected have swelled in 10 years to over 1500 captive individuals, and Parks Australia is exploring options beyond captivity.

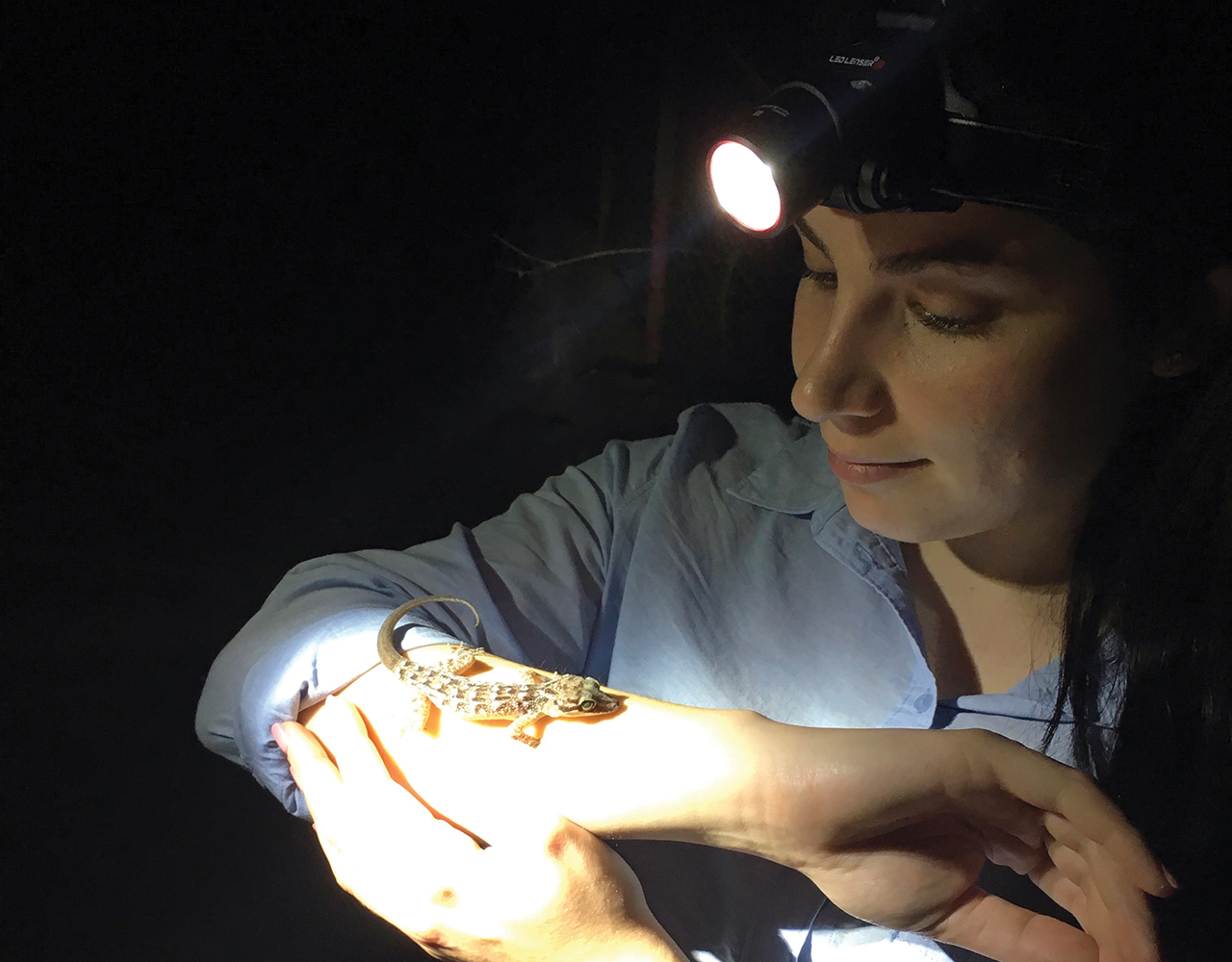

Jessica Agius and supervisor David Phalen analyse samples for pathogens. Image: Jon-Paul Emery

Trial reintroduction

The first of these explorations was trialling blue-tailed skinks in a 2600 m2 semi-wild enclosure on Christmas Island, which was surrounded by a 1m-high barrier designed to exclude wolf snakes, rats and giant centipedes. In April 2017, Parks Australia released 139 blue-tailed skinks into the exclosure and hub PhD candidate Jon-Paul Emery from the University of Western Australia monitored the new population. Jon-Paul recorded a gradual decline in their numbers, and by September 2017 none were detected. While there was no obvious cause of decline, monitoring also recorded large numbers of introduced giant centipedes. Despite efforts to remove them through active searches and trapping prior to and post release, centipede numbers could not be suppressed. As the centipedes had been on Christmas Island for at least 100 years, they had not previously been considered the primary threat to the skinks, but they are ferocious predators capable of preying on vertebrates much larger than themselves.

Jon-Paul undertook an experiment exposing skinks in smaller enclosures to a density of centipedes that matched that of the exclosure for three months and found that it reduced the survival of the skinks by over 30%. Christmas Island National Park staff consequently made great efforts over the next six months to eradicate centipedes from the reintroduction site, in preparation for another trial. Parks staff and Jon-Paul also added an estimated 20 tonnes of logs and branches, 10 tonnes of rock, ceramic tiles and wooden pallets to the site, to improve its habitat suitability.  Jon-Paul during monitoring of the first trial reintroduction. Image: Jon-Paul Emery

Jon-Paul during monitoring of the first trial reintroduction. Image: Jon-Paul Emery

Second trial

With centipedes removed and habitat made more suitable, in early August 2018, 170 blue-tailed skinks were released into the site. Before the release, the animals were weighed, measured and toe-clipped for unique identification, and inspected for signs of the Enterococcus bacterium (see below). Now, 12 months post-release, mark-recapture of more than 200 additional individuals has shown that the population in the trial area has increased substantially. The continuing success of this trial provides for another insurance population of skinks on Christmas Island, has helped resolve the main threats, and has shown that – at least at small scale – those threats can be successfully controlled.

Their own tropical island

A new stage of recovery action for the blue-tailed skink is underway. In September 2019, Parks Australia, supported by the Shire and community of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, introduced 300 skinks to the tiny uninhabited Pulu Blan Island (2.08ha) in the Cocos (Keeling) Island group. The first 150 skinks came from the captive breeding program at Taronga Zoo, and were followed soon afterward by an additional 150 skinks from the captive breeding program on Christmas Island. The release was made possible following successful rat eradication on the island by Parks Australia in January 2019. Hub Masters student Kristen Schubert from the University of Western Australia will monitor the released animals and make comparisons between the survival of animals from the different breeding programs. A second release to another island in the Cocos group, Pulu Kembang (3.38ha), is planned for early 2020.

Assessing reptile health on Christmas Island

Infectious diseases are an increasing threat to wildlife populations worldwide, and have been associated with species declines and extinctions, particularly on islands. In 2014, an Enterococcus bacterium was discovered in the captive breeding population of Lister’s geckos on Christmas Island and resulted in the death of over 40 individuals. This outbreak prompted a more in-depth health analysis of Christmas Island reptiles, which was undertaken by PhD candidate Jessica Agius from The University of Sydney. The assessment additionally discovered two papillomaviruses and several parasites in both invasive and endemic geckos.

The bacterium

The Enterococcus bacterium results in inevitable death of infected animals. Screening has revealed that, fortunately, introduced geckos on Cocos Islands, the site of the recent skink introduction, are not affected. Antibiotics have been trialled on invasive geckos on Christmas Island to see whether Parks Australia could treat infected animals, and while some promising results were achieved, those results also suggested the bacterium may be highly resistant to the antibiotics. This disease therefore threatens the conservation management of the Critically Endangered reptiles on Christmas Island, and poses a high biosecurity risk.

The viruses

The discovery of two papillomaviruses in Christmas Island lizards is the first report of papillomavirus in lizards globally. The papillomavirus and Enterococcus bacterium showed in some animals at the same time, meaning they may work together to cause disease. A diagnostics test to detect the viruses in apparently healthy animals has been developed, and continuing research is seeking to unravel the effects of these viruses on Christmas Island lizards.

The parasites

During the health assessment several internal and external parasites were found: mites, tapeworms, lungworms, roundworms, flukes and coccidia. Infestation by parasites can cause damage to the reptiles’ internal organs, increase their susceptibility to disease and, in some cases, cause death.

Cocos Islands and Christmas Island reptiles are equally affected by parasites, so understanding them will be valuable to managing populations on both Christmas Island and the Cocos Islands.

The semi-wild enclosure on Christmas Island provides 2600m2 of habitat but excludes non-native Asian wolf snakes. Image: Alex Jensen

What’s next for Christmas Island reptiles?

The reintroduction of blue-tailed skinks into Christmas Island exclosures has been successful to date, and continued monitoring will help us to evaluate longer-term success. It is early days for the skinks on Pulu Blan, but monitoring will reveal the outcomes of that trial.

The disease research will now attempt to understand more about the genome of the Enterococcus bacterium, its resistance to antibiotics, and the most effective antibiotic treatments.

We will also continue our investigation into the impact of introduced species on the Lister’s gecko and blue-tailed skink, which stand as fascinating examples of millions of years of reptile evolution in the isolation of Christmas Island.

This Threatened Species Recovery Hub project is a collaboration between Parks Australia (Christmas Island National Park), the University of Western Australia, Charles Darwin University, The University of Sydney, Taronga Conservation Society Australia, the Australian Registry of Wildlife Health, Taronga Zoo and the Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment, with input and advice from the Christmas Island Reptile Advisory Panel (a committee of Parks Australia staff and independent experts). The project is supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program.

For further information

Jon-Paul Emery - jon-paul.emery@research.uwa.edu.au

Jessica Agius - jessica.agius@sydney.edu.au

Top image: Blue-tailed skink. Image: Jon-Paul Emery

-

New territory for Christmas Island reptile conservation

Monday, 07 August 2017 -

Success, failure and lessons learned on Australian islands

Wednesday, 04 May 2016 -

Christmas Island a high priority for the Hub

Sunday, 13 December 2015 -

Protecting threatened Christmas Island reptiles from a new disease

Wednesday, 28 October 2020