Protecting threatened Christmas Island reptiles from a new disease

Wednesday, 28 October 2020Discovering a new species can be a very cool thing, unless that species is a bacterial disease which threatens other species that you are striving to save. University of Sydney researcher Jessica Agius takes a look at a new disease threatening Christmas Island reptiles and her work to combat it.

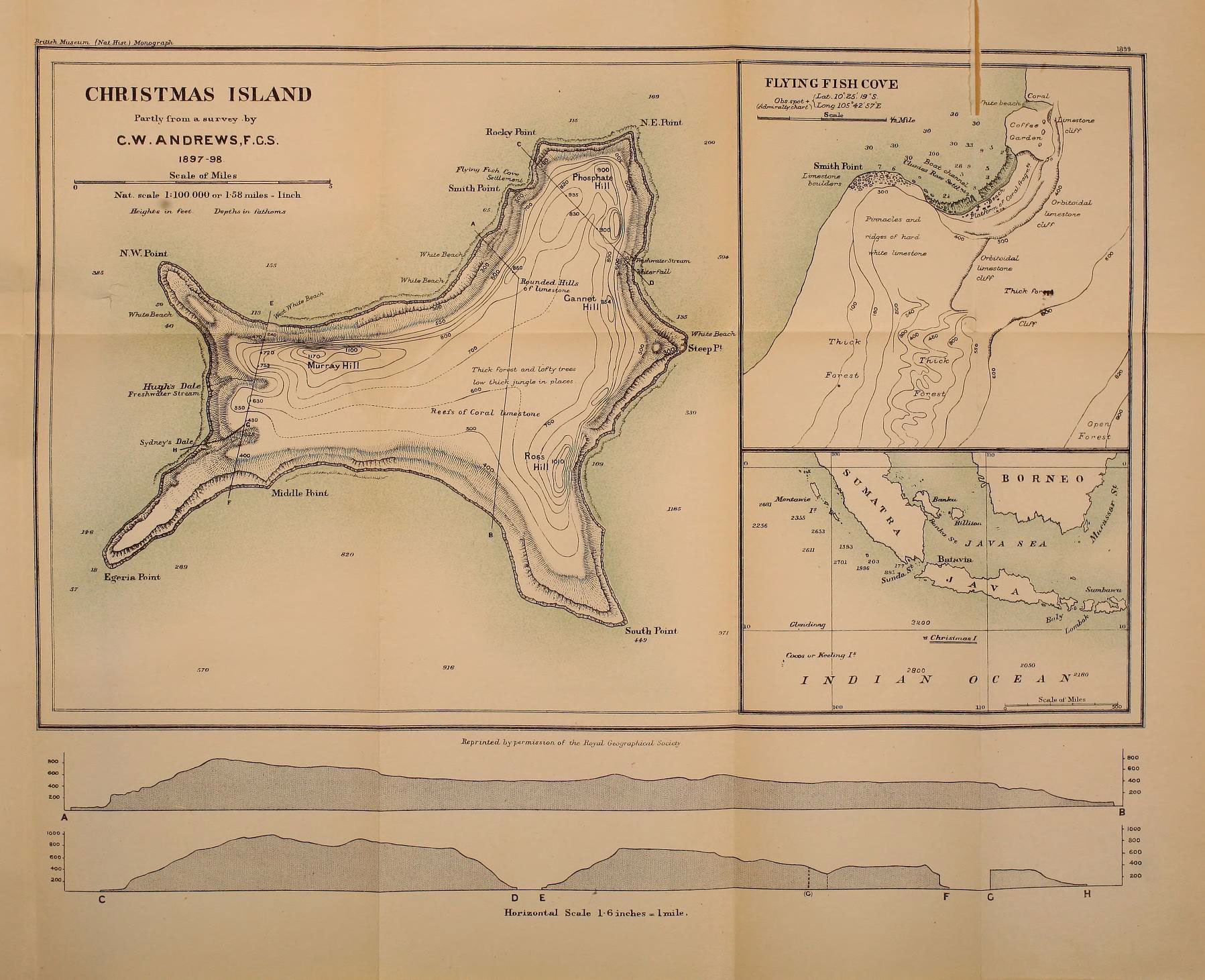

Recent decades have seen major declines in many of Christmas Island’s native reptiles. Although once abundant and widespread, the Lister’s gecko (Lepidodactylus listeri) and the blue-tailed skink (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) have disappeared from the wild. A key cause of the declines is believed to be predation by invasive species, like the Asian wolf snake and giant centipede.

The skink and gecko have been thriving in captive breeding programs where they are protected from these threats, but in 2014 some captive animals started getting sick. The cause was discovered to be a new strain of bacteria (Enterococcus lacertideformus), which grows in the tissues of the head then the internal organs, before eventually causing death.

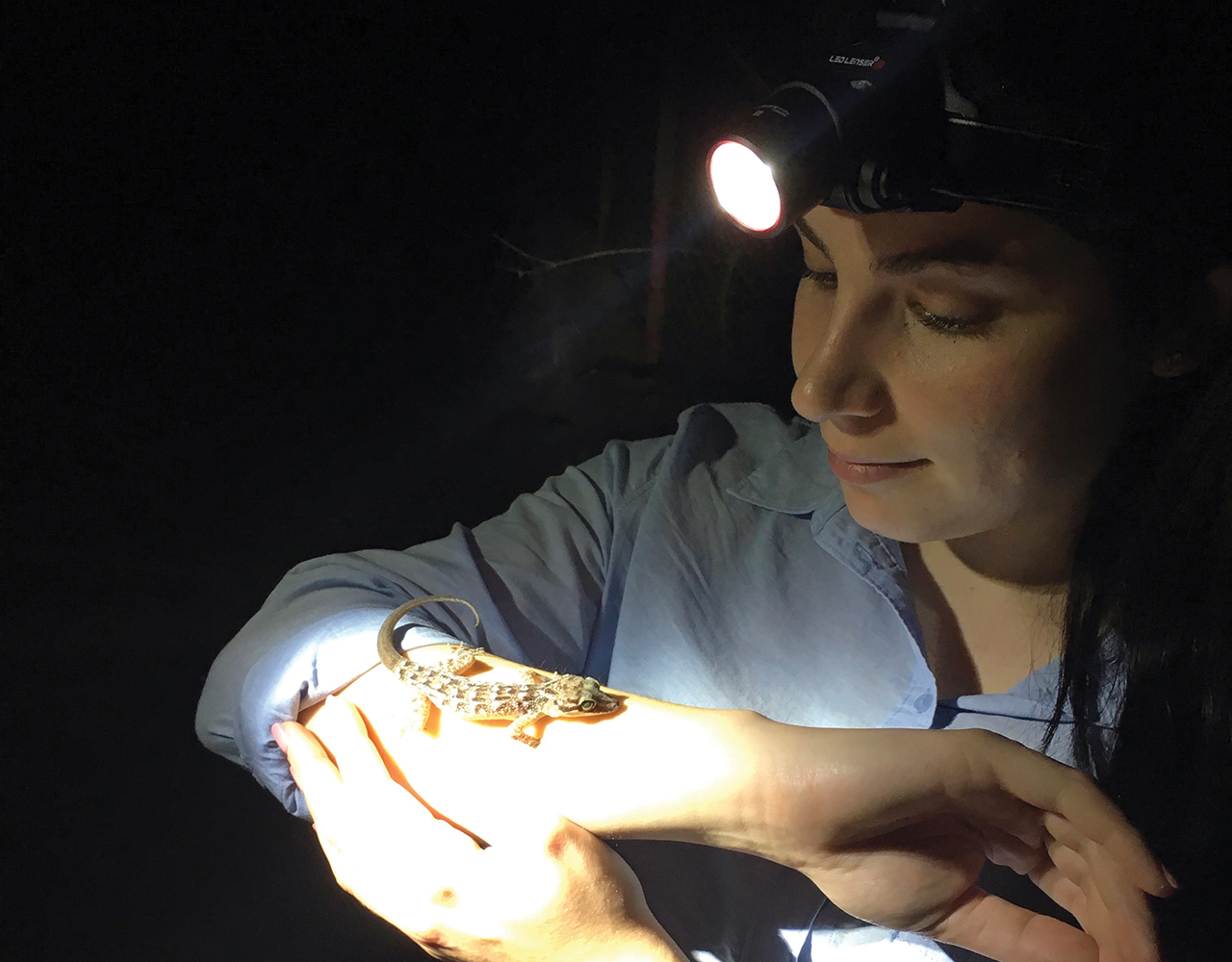

Taking a gecko at translocation

Island-wide surveys revealed that the disease is also present among two invasive non-native gecko species on Christmas Island: Asian house geckos (Hemidactylus frenatus) and mute geckos (Gehyra mutilata). It is likely that contact with infected invasive geckos has been the cause of outbreaks of the disease in captive blue-tailed skink populations housed in outdoor pens since 2014.

Given the persistence of the disease in wild invasive gecko populations, introducing the two native species to locations other than Christmas Island is an important “insurance” strategy. Blue-tailed skinks were recently introduced to the nearby Cocos (Keeling) Islands in a successful translocation; and, to safeguard both native species, the possibility of further introductions to Cocos Islands, or other locations with comparable environments to Christmas Island, is also being explored.

How is infection caused?

To learn about the disease, we collected invasive Asian house geckos from the wild on Christmas Island and undertook experimental trials on them. The disease appears to need direct contact to cause infection. Infection generally follows if an animal eats infected tissue or gets infected tissue in contact with its mouth or broken skin – things that commonly occur when geckos fight, particularly during mating.

This means that healthy captive animals need to be kept apart from infected geckos and should also be kept away from areas where infected animals have been.

We found that progression of the disease is slow and highly variable, with the visible signs first showing six to 14 weeks after infection. This complicates the management of the disease, as infected animals may appear to be healthy for many weeks. It also has implications for quarantine; if captive animals are to be translocated, a minimum quarantine period of 16 weeks will be necessary to prevent spread of the disease.

The future

Antibiotics are one potential way to control this disease, although a treatment trial we conducted was not successful. We could not cure geckos infected with the disease, even after three weeks of intense treatment. Geckos with minimal lesions responded better to antibiotics, but were still infected at the end of the treatment course. But until a universally effective antibiotic treatment is found, control of this deadly disease and long-term conservation of the captive species will depend heavily on strict quarantine and biosecurity practices, and the establishment of threatened populations to locations other than Christmas Island.

Further information

Jessica Agius - Jessica.agius@sydney.edu.au

Work cited

Rose, K., Agius, J., Hall, J., Thompson, P., Eden, J. S., et al. 2017. Emergent multisystemic Enterococcus infection threatens endangered Christmas Island reptile populations. PLOS ONE 12(7): e0181240. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181240

Top image: Jessica Agius in the field spotlighting geckos on Christmas Island. Image: David Phalen