National review and workshop put spotlight on plant translocation

Tuesday, 08 August 2017Last week, the TSR Hub in collaboration with the Australian Network for Plant Conservation brought together leading plant conservation experts from every state and territory to review the national guidelines for plant translocation. The review will keep Australia at the cutting edge of this important technique used in the fight against plant extinctions.

The work builds on a review led by TSR Hub researchers Dr David Coates and Dr Jennifer Silcock of over 850 plant translocations of 400 species undertaken in Australia in the past 40 years. This includes Australia's first plant translocation for conservation of Jumping-jack Wattle at the Lonsdale Nature Reserve in Victoria.

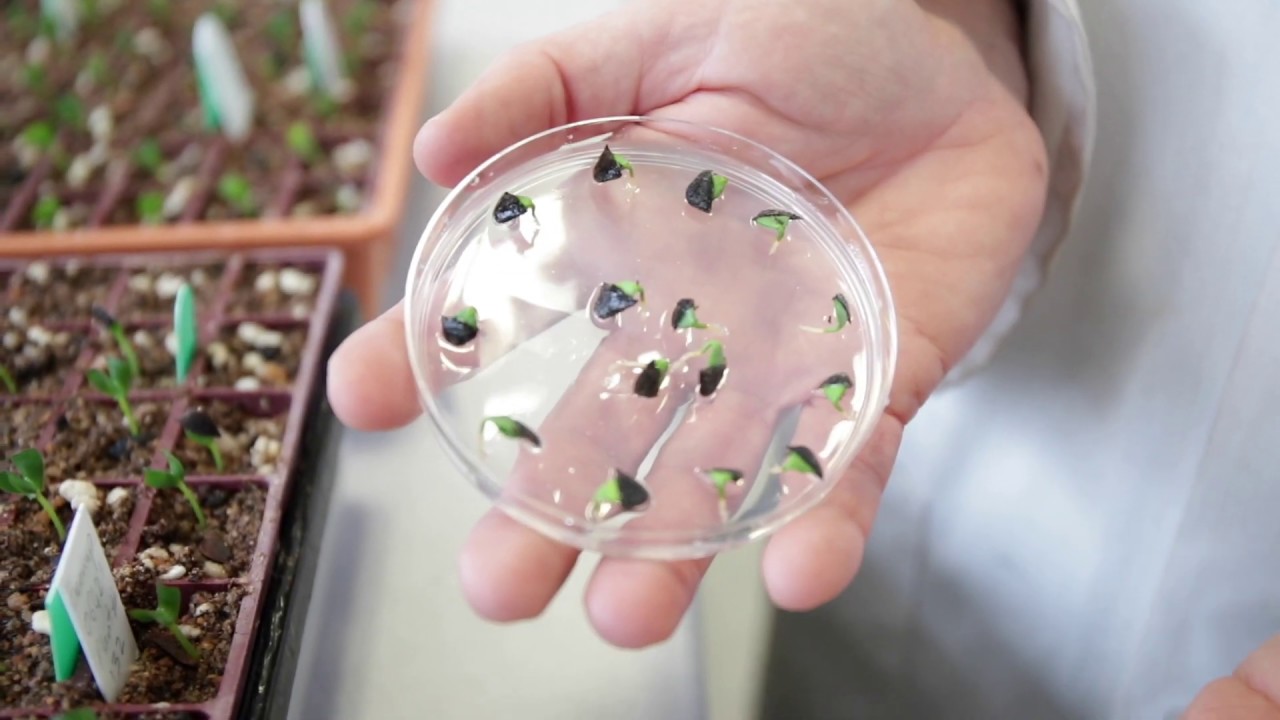

Plant translocation, the deliberate movement of plants, is the plant equivalent of captive breeding and release programs. It is a relatively new but rapidly growing field, which is often used together with more traditional conservation approaches such as bush regeneration and weed management.

It is often used to create ‘insurance populations’ of species that are very rare or have a very small distribution, in case threats like fire, phytophthora or development wipe out the original plants. For example, the Nielson Park She-oak from Sydney Harbour now only remains in translocated populations.

Many Commonwealth and state conservation programs including the Threatened Species Strategy, 20 Million Trees, Landcare, parks organisations, botanic gardens and Saving Our Species (NSW) are already undertaking plant translocations.

Jumping-jack Wattles (Acacia enterocarpa) have thrived at Lonsdale Nature Reserve, Victoria, since they were planted in 1976. Photo Jennifer Silcock

But there is more to the technique than just planting things, each plant can require many complex factors for the translocation to succeed. This is a point well illustrated by work to the conserve Mellblom’s Spider-orchid in far south-west Victoria, led by Dr Noushka Reiter at the Royal Botanic Garden Victoria.

“Mellblom’s Spider-orchid lures male thynnid wasps by mimicking the sex pheromones of the female wasp. Wasps pick up pollen when they try to mate with the flower and take it to the next orchid where they are tricked again,” said Dr Reiter.

“There is no point translocating the orchid to areas that don’t have the wasp – and it isn’t common - so in 2014 we used surveys to identify two remaining orchid areas that still have thynnid wasps.”

“We then worked with many partners including volunteers from the Australasian Native Orchid Society of Victoria to translocate almost 450 orchids, which were grown at the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, to those sites over the last three years.

“It has been a success - we are seeing natural pollination and seed set at both sites,” said Dr Reiter who presented at the national workshop.

“The success is due to many partners including Parks Victoria, Alcoa/ Portland Aluminium, Australian Network for Plant Conservation and enthusiastic community groups."

Last week's translocation event was jointly hosted by the TSR Hub, the Australian Network for Plant Conservation, the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage and the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney.

As well as the 2 day review workshop there was a public information day on 1 August. The fully booked day attracted 80 attendees, many from NRM and park management organisations and volunteer bush conservation groups.

Top image: Mellblom's Spider-orchid (Caladenia Hastata). Photo: Noushka Reiter

-

Saving an Endangered wattle: Translocating Acacia cochlocarpa

Monday, 20 July 2020 -

Seed bank saving species in Western Australia

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Guidelines for the Translocation of Threatened Plants in Australia

Wednesday, 29 July 2020 -

Managing the genetics for a new population of a threatened plant

Monday, 12 April 2021

-

Fire a vital ingredient for the recovery of a Critically Endangered wattle

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

David Coates: A dedication to Australia's plantlife.

Sunday, 11 November 2018 -

Hundreds of translocations but who's counting?

Thursday, 08 September 2016 -

Learning from plants going places in Australia

Monday, 02 October 2017 -

Plant translocation: New guidelines a game changer

Sunday, 11 November 2018 -

Race against time for Endangered leek orchids

Sunday, 11 November 2018 -

Race to unlock secret to save endangered orchids

Wednesday, 22 August 2018 -

Sowing the seeds of success

Monday, 23 May 2016 -

Species on the move conference

Monday, 28 March 2016