Sowing the seeds of success

Monday, 23 May 2016Hungry herbivores, fungal diseases and long hot summers are just a few of the challenges land managers face when attempting to re-introduce a threatened plant species. But the biggest challenge of all may lie in calculating whether a reintroduction program has been successful.

“When we reintroduce a threatened plant species, we do so with the goal of creating a viable population that will be self-sustaining into the future,” says project leader Dr David Coates, from the Department of Parks and Wildlife, WA.

“The aim of our project [Project 4.3] is to examine the methods we use in our programs, in order to improve our success rates.”

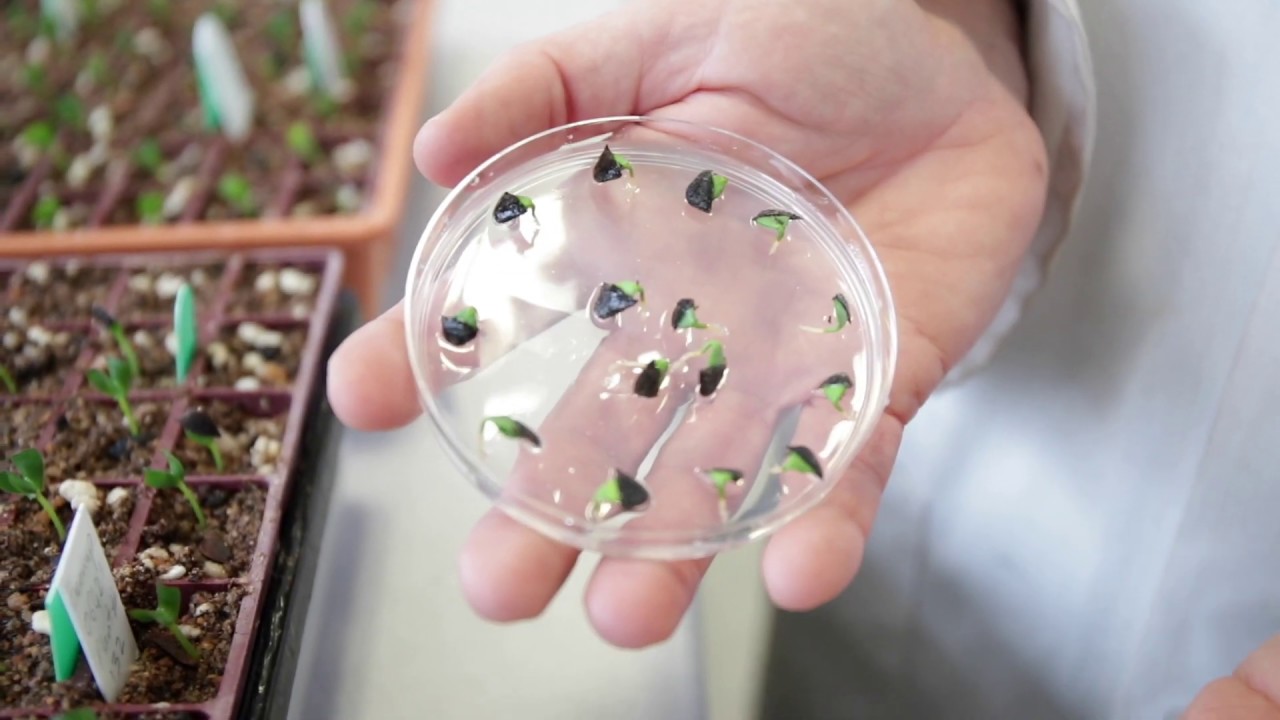

Dr Coates and his team face a series of inter-related problems that begin with the challenges of propagation.

“Some of these species require unusual techniques to get them going, for example we need to use fire to extract the seeds from banksia cones.

“Sometimes seeds don’t propagate easily, either due to the specific soil mix or the difficulty of creating the right conditions. And other times we just don’t know why a particular species struggles to get going.

“We must always remain conscious that in the case of particularly rare species, we don’t have large amounts of seed to begin with, so we need to be very careful. Our margin for error is small.”

Even if the propagation is successful, the team must work to find a suitable habitat to reintroduce the young plants, and ensure there are no immediate threats.

“In Western Australia we are always on the lookout for dieback, which is an introduced pathogen and devastating soil-borne fungal disease. For the most part we can’t really combat it, other than by preventing access by people to affected areas to minimise its spread,” says Dr Coates.

“Both feral and native animal grazing are also threats, they are typically curious about our activities and have a taste for young seedlings. If we don’t fence them out, they will eat everything.

“We also need to keep an eye on the weather. Long hot summers can quickly undo all of our hard work and initial watering may be needed to assist establishment.”

In order to achieve the ultimate goal - a self-sustaining and viable population, a critical number of plants must survive to reproductive maturity.

“This will be a major focus of our research, looking at ways we can both measure and model levels of pollination, reproduction, recruitment and genetic variation. This will be challenging in some cases where the lifespan of a number of the shrubs and trees will usually outlast the lifespan of any given project.”

“We can then benchmark these results against natural populations.”

“It’s essentially a numbers game, where we need to discover how many plants need to be established in order to ensure a species’ survival. At the moment we aim for at least 250, but depending on the species, we may need many more.”

“Our research aims to provide the answers to these questions.”

Image: Lambertia orbifolia - Round-leaf Honeysuckle by Tatters/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

-

Saving an Endangered wattle: Translocating Acacia cochlocarpa

Monday, 20 July 2020 -

Seed bank saving species in Western Australia

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Guidelines for the Translocation of Threatened Plants in Australia

Wednesday, 29 July 2020 -

Managing the genetics for a new population of a threatened plant

Monday, 12 April 2021

-

Plants in the ashes: Prioritising Australian flora after the fires

Monday, 31 August 2020 -

Fire a vital ingredient for the recovery of a Critically Endangered wattle

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

David Coates: A dedication to Australia's plantlife.

Sunday, 11 November 2018 -

Hundreds of translocations but who's counting?

Thursday, 08 September 2016 -

Learning from plants going places in Australia

Monday, 02 October 2017 -

National review and workshop put spotlight on plant translocation

Tuesday, 08 August 2017 -

Plant translocation: New guidelines a game changer

Sunday, 11 November 2018 -

Race against time for Endangered leek orchids

Sunday, 11 November 2018 -

Race to unlock secret to save endangered orchids

Wednesday, 22 August 2018 -

The fire, the fox and the feral cat

Tuesday, 06 June 2017 -

Threatened Species Recovery Hub statement on the fires

Tuesday, 14 January 2020 -

Why Buloke woodland species are failing to regenerate

Friday, 20 October 2017 -

Species on the move conference

Monday, 28 March 2016