Plants in the ashes: Prioritising Australian flora after the fires

Monday, 31 August 2020Australia has one of the highest rates of plant endemism of any country globally. After the catastrophic fire season of 2019–20, Dr Rachael Gallagher and Professor David Keith are leading two teams to find out which species and ecological communities are most in need of immediate recovery.

During the 2019–20 bushfire season, over 12 million hectares of Australia burned. Many thousands of species were affected, and much focus has been on the rescue and care of Australia’s animals. Yet Australia is home to around 25,000 native plant species, most of which are endemic and many that had more than 90% of their range burnt.

While many Australian plants are adapted to fire and thrive through resprouting and fire-induced seed germination, the fires have compounded the effects of other threats such as drought, grazing, disease or flooding, or made many plants more susceptible to those threats. This may significantly increase the risks of local, and even global, extinction. Australia’s plant communities face similar issues and there is an urgent need for on-ground actions and legislative protections to ensure their survival.

Image: The resprouting and germination currently underway may be jeopardised by the cascading effects of post-fire drought, grazing, weed invasion or disease. Image: Anne Kerle

Image: The resprouting and germination currently underway may be jeopardised by the cascading effects of post-fire drought, grazing, weed invasion or disease. Image: Anne Kerle

A national prioritisation exercise is providing an evidence base for decision-making to inform the work of the Wildlife and Threatened Species Bushfire Recovery Expert Panel chaired by the Threatened Species Commissioner. The prioritisation is based on 11 criteria developed by Dr Tony Auld and colleagues within the New South Wales Department of Planning, Infrastructure and Environment to identify species suffering the greatest likely impacts. The criteria first ask how much of the distribution of each species or community fell within the area burnt by the 2019–20 fires. For the 19,004 plants so far assessed, up to 11,887 likely have some part of their range burnt, and 76–136 more than 90% burnt. These estimates are based on three complementary lines of evidence about species’ ranges: herbarium occurrence data; modelled distributions based on climates and soils; or – for species listed under the EPBC Act – regulatory maps. Using multiple sources to estimate species’ ranges helps to prevent over- or underestimating where plants occur in the landscape. Although knowing how much of the species range may have been burnt is crucial, it is just part of the puzzle for understanding the impacts.

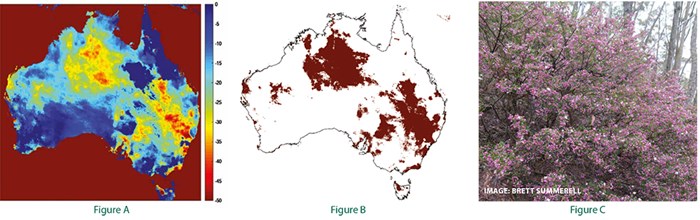

Threats affecting fire recovery in plants For many species, the bushfires were an additional stressor that worsened the effects of other threats affecting plant recruitment, growth and survival. In recognition of this, several of the 11 criteria concern the interacting effects on species of threats like drought, disease, grazing, weed invasion and changing temperatures. For instance, plants that have lost carbohydrate reserves because of prolonged drought conditions may struggle to resprout after fire, particularly if their storage or regenerative organs have been damaged. Pre-fire drought can also slow down reproduction, reducing the size of the seed bank available for post-fire recruitment. To assess this risk, we coupled plant and ecological community distribution data to estimates of the accumulated severity of drought in the year before the fire season (see Figures A and B). Accumulated drought severity was based on the Standardised Precipitation Index, which measures the variation in precipitation relative to the average.

Of the species we examined so far for the prioritisation, we considered 176 to be at high risk from pre-fire drought interacting with the impact of fire.

The ability of these species, such as the shrub Boronia imlayensis, to resprout after the fires may be seriously compromised by pre-fire drought. The Mount Imlay Boronia (Figure C) – which is currently not listed as threatened – has a highly restricted range, at least 96% of which was burnt. Unless its populations recover adequately, this species is now at risk of extinction. Other interacting threats may limit the capacity of species to recover, such as high fire frequency (Criteria B and K), browsing and grazing of regenerating shoots (Criterion C) and the impact of diseases, such as myrtle rust and Phytophthora root rot, on regenerating plants (Criterion D). For instance, the Eastern Stirling Range Montane Heath and Thicket Threatened Ecological Community (TEC) is currently listed as Endangered in the EPBC Act and was entirely burnt. Importantly, most of the TEC had also been burnt 18 months earlier, leaving little time for adequate recovery.

Further, it is faced with significant risk from root rot disease, which seems to have even greater impacts on plant survival post-fire. Ongoing analyses are showing that some locations in New South Wales and Western Australia have intervals between fires that are likely too short for recovery of the vegetation. Species in these areas are likely to become locally extinct and replaced by species with short generation times or non-woody underground root stalks, unless there are no further fires in the near future.

A) Accumulated severity of drought conditions in December 2019 over the previous 12-month period. More negative values correspond to more severe drought;

(B) Classification of areas of significant pre-fire drought conditions used to assess against Criterion A – Interactive effects of fire and drought;

(C) Boronia imlayensis had more than 95% of its range burned amid existing threats from prolonged drought conditions.

Cooperation across borders

The national prioritisation for plants and TECs involves cooperation across jurisdictions, with many agency staff from fire-affected states and territories providing data and knowledge, alongside the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. For instance, agencies have shared and integrated data on plant traits and fire extent to provide a more comprehensive picture of impact, while also helping to identify key gaps in our knowledge. The process has highlighted the need for rapid delivery of fire-mapping products and standardised national data about how plants respond to fire.

Assessing extinction risk against IUCN Red List criteria for fire-affected plants and ecosystems will also require collaboration, with experts contributing their knowledge and data. We have already prioritised 471 plant species and 19 TECs for the $12 million Wildlife and Habitat Bushfire Recovery Program. Many of these species need on-ground research to gather evidence about population size, threats and decline for listing under the EPBC Act or state legislation. Although ex-situ collection of seed material may be necessary in rare cases, the seed banks of the affected species should be allowed to replenish after the fires. This means avoiding follow-up fires for the next few years and preventing over-harvest of flowers and seed.

Given the richness of the Australian flora and the vast area of the continent, a collaborative approach to ecological research has never been more important. A combination of boots on the ground, fingers on the laptops and minds on the analysis of data will be crucial to recovering Australian vegetation for the future.

Further information

Rachael Gallagher - Rachael.gallagher@mq.edu.au

David Keith - David.keith@unsw.edu.au

Further reading

https://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/bushfire-recovery/priority-plants

Top image: New shoots start the long road to recovery. Image: Anne Kerle

-

Protecting persistence: Listing species after the fires

Tuesday, 01 September 2020 -

Post-fire recovery of Australia’s threatened woodlands: Avoiding uncharted trajectories

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

‘Tis the season...Understanding how threatened plants respond to different fires

Tuesday, 26 November 2019 -

The fire, the fox and the feral cat

Tuesday, 06 June 2017 -

Threatened Species Recovery Hub statement on the fires

Tuesday, 14 January 2020 -

Sowing the seeds of success

Monday, 23 May 2016 -

Strategic fire management can reduce extinctions

Sunday, 22 November 2015