When rabbits are off the menu, what’s for dinner?

Monday, 16 March 2020Rabbits and feral cats are individually two of the most widespread and destructive pest species in Australia. When rabbit numbers are abundant they also boost feral cat populations. As a result, over the long-term, rabbit bio-controls can be effective in reducing both rabbit and feral cat populations. But what happens when rabbit numbers first crash; do cats prey-switch and create a bigger threat than usual for native wildlife? We asked Dr Hugh McGregor from the University of Tasmania about his landscape-scale experiment at Arid Recovery in South Australia which is tackling these questions.

Rabbits are a major problem for Australia. They are one of our most damaging pests, directly impacting hundreds of threatened species, most of which are plants. With enough time they can level whole woodlands and other habitats, by preventing new trees and plants from regenerating.

In contrast, cats and foxes are a major threat to native animals. Cats are Australia’s most widespread feral predator and negatively impact at least 123 threatened species. Foxes impact at least 95 threatened species. They have been implicated in the decline of most threatened Australian mammal species.

As if these individual impacts were not enough, when they occur in the same area rabbits can also exacerbate the impacts of cats and foxes. This is likely occurring in southern Australia, where abundant rabbit populations support high densities of feral cats and foxes. Like a town providing free food, rabbits provide an endless source of protein, and enable cats and foxes to breed to their maximum capacity, inflating their densities.

A plains mouse at Arid Recovery. Image: Nicolas Rakotopare

Kitchen is closed

But what would happen if an abundant rabbit population is suddenly reduced? Would cat or fox numbers quickly re-stabilise to match lower rabbit densities? Would they temporarily increase their predation on native species?

The most well-known instances of major reductions of rabbits occurred following the release of the bio-control agents myxoma virus in the 1950s and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV, or calicivirus) in the mid-1990s.

In addition to achieving huge reductions in rabbits, these rabbit biocontrols also caused cat numbers to plummet in parts of arid Australia, where they have not rebounded to previous levels since. There is evidence to show that native wildlife benefitted from the reduction in cat numbers. However, when rabbit numbers first crashed, the hyper-abundant cats likely switched to eating native prey while the cat population restabilised to lower levels. Some studies reported more native animals in cat scats after rabbit numbers dropped.

A very large experiment

Our research looked in detail at the short-term response of feral cats when the abundance of rabbits is suddenly reduced. Do they switch from rabbits to other prey? Does the cat population size also suddenly reduce? We did this by conducting a landscape-scale experiment at the Arid Recovery Reserve in South Australia. We removed around 80% of the rabbit population from within a 37 km2 experimental enclosure (2,215 rabbits removed from an estimated population of about 2,800).

To learn how this would affect the resident feral cat population within the enclosure, before the rabbit reduction we caught and GPS collared 30 cats, also putting video collars on many of them. We also collected and analysed scats and monitored the population sizes of cats and small mammals by counting their tracks along transects. From these data we were able to measure the survival, health, diet and hunting rates of the cats before and after the rabbit removal.

To ensure that any changes we observed were due to the change in rabbit numbers and not other factors like weather, we monitored cats and small mammals at both the experimental site and an adjacent control area where rabbits were not removed.

GPS-collaring of feral cats during the study revealed that many cats focus their hunting at rabbit burrows when rabbit numbers are high. Image: Nicolas Rakotopare

Rabbit-hunting specialists

Before the rabbit removal, we could tell rabbits were very important for feral cats. They were found in 80% of cat scats. Data from the GPS and video collars revealed that the hunting strategy of many cats was heavily focused on rabbits, and some GPS data looked like a join-the-dots picture of visits to rabbit warrens. We even recorded a rabbit kill on camera, and it was certainly a larger meal than anything else we saw the cats eat.

The effects of the rabbit removal on feral cats were substantial. Within a month, survival of collared cats decreased by 40%. Cat activity also declined by 40%. Surviving cats lost weight and condition, while we saw no change in cat body condition or activity in the nearby control area where there was no rabbit removal.

Hungry cats will eat carrion

Cat diet also changed substantially; after the rabbit cull, cats were more likely to eat novel food sources like carrion, reptiles and insects. Before the rabbit cull, we had even seen some instances on video collars of cats walking past reptiles and carrion without eating them. However, we did not observe an increase in the consumption of small mammals like plains mice or hopping mice after the rabbit cull.

We showed that prey-switching by cats will occur after rabbit populations are reduced. However, much of this involves switching to foods that are easy to find but were previously not preferred, such as carrion. Cats may be less likely to switch to harder-to-kill prey, such as small native mammals. Given the perilous state of many native mammals, it was heartening to observe that following the rabbit cull impacts on native mammals did not significantly increase. However, the impacts to reptiles and insects in an area could still be significant.

When rabbit numbers are abundant they also boost feral cat populations. Image: Hugh McGregor

A golden opportunity

Managing rabbit populations using biocontrols or warren-ripping leads to long-term reductions in cat populations, but it also creates opportunities for land managers to achieve even greater reductions in feral cat numbers. In particular, while cats do not readily take poison baits in general, they are likely to be extremely effective following a large reduction in rabbits.

Our research has shown that at these times, when their favoured prey is off the menu and cats are hungrier, they will take food sources that they would not otherwise consider, such as carrion and baits.

These findings will be valuable to informing feral cat management in all areas where rabbits are present.

The Threatened Species Recovery Hub project was led by the University of Tasmania in collaboration with Arid Recovery, the Invasive Animals CRC, Ecological Horizons and The University of Queensland. It received funding from the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program.

For further information

Hugh McGregor - hugh.mcgregor@utas.edu.au

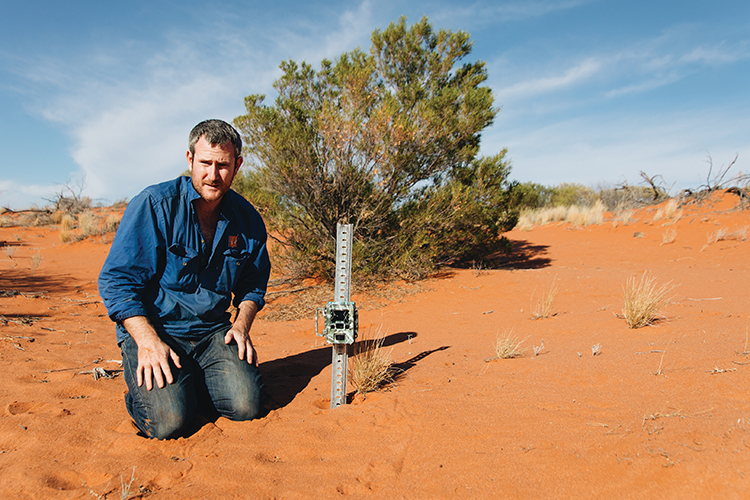

Top image: Hugh McGregor sets up a motion detection camera to monitor feral cats and native mammals at Arid Recovery in South Australia. Image: Nicolas Rakotopare

-

Small mammal declines in the Top End - Causes and solutions

Monday, 31 August 2020 -

Fire, cats, foxes and land management: Lessons learned

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

Cats are killing millions of Australia’s birds

Sunday, 22 October 2017 -

FoxNet: A game changer for fox control

Tuesday, 30 June 2020 -

Hugh McGregor - Comprehending Cats

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

Rabbit burrows helping cats colonise new frontiers

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

Rabbits off the menu for feral cats

Monday, 14 November 2016 -

Testing cat baiting on Kangaroo Island

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

The fire, the fox and the feral cat

Tuesday, 06 June 2017 -

Tiwi Island mammals: Saving the brush-tailed rabbit-rat

Tuesday, 11 September 2018 -

When the cat’s away will the rats play?

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

Threatened Species Recovery Hub to join fight against feral cats

Tuesday, 03 November 2015 -

TSR contributes to Feral Cat Taskforce

Monday, 28 March 2016 -

Cat science finalist for Eureka Prize

Monday, 28 September 2020