Testing cat baiting on Kangaroo Island

Monday, 16 March 2020A feral cat eradication program is underway on Kangaroo Island. Conservation managers want to know if poison baiting is suitable for densely vegetated and inaccessible areas characteristic of most of the island’s conservation reserves. To answer this question, Dr Rosemary Hohnen from Charles Darwin University undertook a trial of non-toxic Eradicat® feral cat baits to test the risk to native animals and uptake by cats.

The Australian Government has a plan to eradicate feral cats on five Australian islands by 2020, the largest of which is Kangaroo Island (4,405 km2). Kangaroo Island is home to many endemic species and subspecies, including the Kangaroo Island dunnart and Kangaroo Island echidna and is a stronghold for some species that are declining on the mainland, including Rosenberg’s goanna, the pygmy copperhead and the southern brown bandicoot.

Eradicating cats will benefit these species and will also benefit the island’s agricultural sector, by reducing cat-borne parasites, which cost the island’s sheep industry at least $2 million per year. The eradication program has already begun and is being led by Natural Resources Kangaroo Island and the Kangaroo Island Council, with the support of the South Australian and Australian Governments.

Used in conjunction with other approaches, poison baiting is a useful tool for feral cat eradication, and is one that could be particularly useful in the (formerly) densely vegetated and hard-to-access areas of western Kangaroo Island. The need to effectively manage cats on western Kangaroo Island is now even greater, as they are likely to be concentrating their foraging in the small patches of vegetation that remain after the January 2020 fire, some of the last habitat left for threatened small mammals like the Kangaroo Island dunnart. The 1080-based bait Eradicat® has been used widely in south-west Western Australia, where native plants naturally contain the toxin, and native mammals have a higher tolerance to 1080 than introduced species. However, the toxin does not occur at high concentrations in the flora of Kangaroo Island, so native animal species may have low tolerance.

Hence, prior to any broadscale baiting, it is important to test whether native animals would consume the baits.

Non-toxic trial

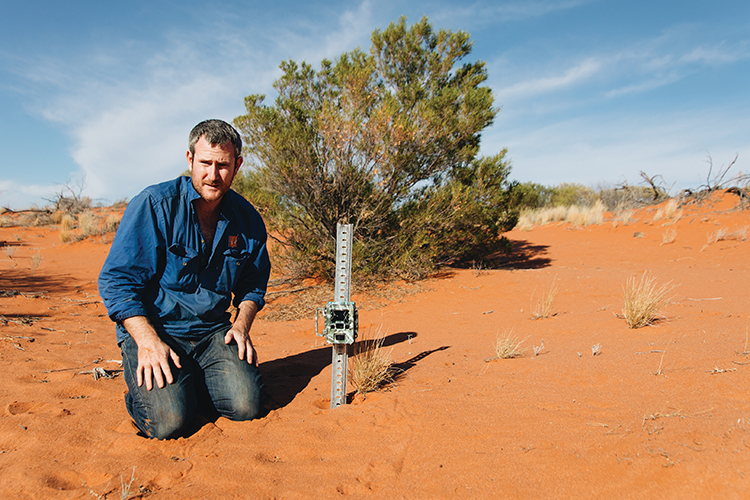

We undertook a trial of non-toxic Eradicat® baits. We deployed 288 baits across four sites within Flinders Chase National Park and Ravine des Casoars Wilderness Protected Area in August and again in November 2018. Baits were placed in open areas in front of motion-activated camera traps, which recorded which species approached the baits.

For this trial, the baits also contained Rhodamine B, because this dye can be traced to assess whether animals have consumed the bait: in this case, the dye is deposited in whiskers after consumption. Two to three weeks after each baiting period we trapped for six nights and took whisker samples to see if animals had consumed baits.

We found that many native animals consumed the baits: from whisker samples we saw that almost all brushtail possums caught during trapping had consumed baits; over half of the bush rats; and one-third of the western pygmy possums. Australian ravens, Rosenberg’s goannas and southern brown bandicoots were also recorded approaching baits by the camera traps.

No Kangaroo Island dunnarts and only one southern brown bandicoot were captured during trapping, so bait uptake could not be determined. While the number of times these species approached baits was few, this may reflect the very low abundance of these species rather than lack of interest in the baits.

Low uptake by cats

Cats took less than 1% of the baits; they approached the baits only six times during the trial and took only one bait. This could reflect either an aversion to scavenging when live prey are readily available, which has been observed in feral cats in some parts of Australia, or the area over which the trials took place being smaller than the normal ranging area of a feral cat.

Overall, these results suggest that Eradicat® would be an unsuitable choice of bait for broadscale feral cat control on Kangaroo Island. Two other feral cat baits that are currently in development, Curiosity® and Hisstory®, may have lower impacts on native wildlife. This is because the poison is contained in a hard capsule in the middle of the sausage bait. While cats are expected to eat the entire bait, smaller native wildlife are expected to chew around and then discard the encapsulated poison pellet.

However, as we saw only low uptake of baits by feral cats, potentially the baits need to be deployed at a time of year when cats are hungrier, and/or at a higher density than was used in this study (60 baits per km2) to increase the likelihood of cats encountering and consuming them.

This project was led by Charles Darwin University, working collaboratively with the South Australian Department for Environment and Water, Natural Resources Kangaroo Island, Australian National University, The University of Queensland and The University of Sydney.

For further information

Read the findings factsheet

Rosemary Hohnen – rosie.hohnen@gmail.com

Sarah Legge – sarah.legge@gmail.com

Top image: A brushtail possum eating one of the non-toxic baits in front of a camera trap. Image: Rosemary Hohnen

-

Combating a conservation catastrophe: Understanding and managing cat impacts on wildlife

Tuesday, 06 October 2020 -

Cat-borne diseases and their impacts on human health

Monday, 19 October 2020 -

Cat-borne diseases and their impacts on agriculture and livestock in Australia

Monday, 07 December 2020 -

li-Anthawirriyarra Sea Rangers managing cats on West Island

Thursday, 16 September 2021 -

The impact of roaming pet cats on Australian wildlife

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Kangaroo Island Post-fire Wildlife Recovery Workshop

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Finding the Kangaroo Island dunnart

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Caring for Country: Managing cats

Tuesday, 09 November 2021

-

Small mammal declines in the Top End - Causes and solutions

Monday, 31 August 2020 -

Fire, cats, foxes and land management: Lessons learned

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

Addressing our wildlife cat-astrophe

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

Cats are killing millions of Australia’s birds

Sunday, 22 October 2017 -

Detecting and protecting the Kangaroo Island dunnart

Monday, 24 September 2018 -

Feral cats: An Australian Government perspective

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

FoxNet: A game changer for fox control

Tuesday, 30 June 2020 -

In search of the KI dunnart – Island conservation after the feral cat

Tuesday, 06 June 2017 -

Researcher Profile: Rosemary Hohnen

Wednesday, 05 June 2019 -

The conundrum of cats in Australia

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

The fire, the fox and the feral cat

Tuesday, 06 June 2017 -

The mathematics of cats

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

The unnoticed toll of cats on reptiles

Monday, 25 June 2018 -

Tiwi Island mammals: Saving the brush-tailed rabbit-rat

Tuesday, 11 September 2018 -

Tracking cats to help the night parrot

Wednesday, 05 June 2019 -

When rabbits are off the menu, what’s for dinner?

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

When the cat’s away will the rats play?

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

Threatened Species Recovery Hub to join fight against feral cats

Tuesday, 03 November 2015 -

TSR contributes to Feral Cat Taskforce

Monday, 28 March 2016 -

One cat, one year, 110 native animals: Lock up your pet, it’s a killing machine

Wednesday, 28 October 2020 -

Cat science finalist for Eureka Prize

Monday, 28 September 2020 -

Cats have $12 million impact on agriculture in Australia

Monday, 07 December 2020 -

Cat diseases have $6 billion impact on human health in Australia

Thursday, 15 October 2020