5 lessons for more effective conservation messaging

Wednesday, 28 October 2020Building community support for conservation is crucial for achieving successful outcomes. Communication activities are an important part of building this support and are used to encourage specific behaviour changes, such as getting more people to keep their pet cats inside. How we say stuff can have a big influence on how effective our communications are. Alex Kusmanoff and colleagues at RMIT University have five lessons that can help conservation managers and researchers make their messages more effective.

1. How you say something can be as important as what you say

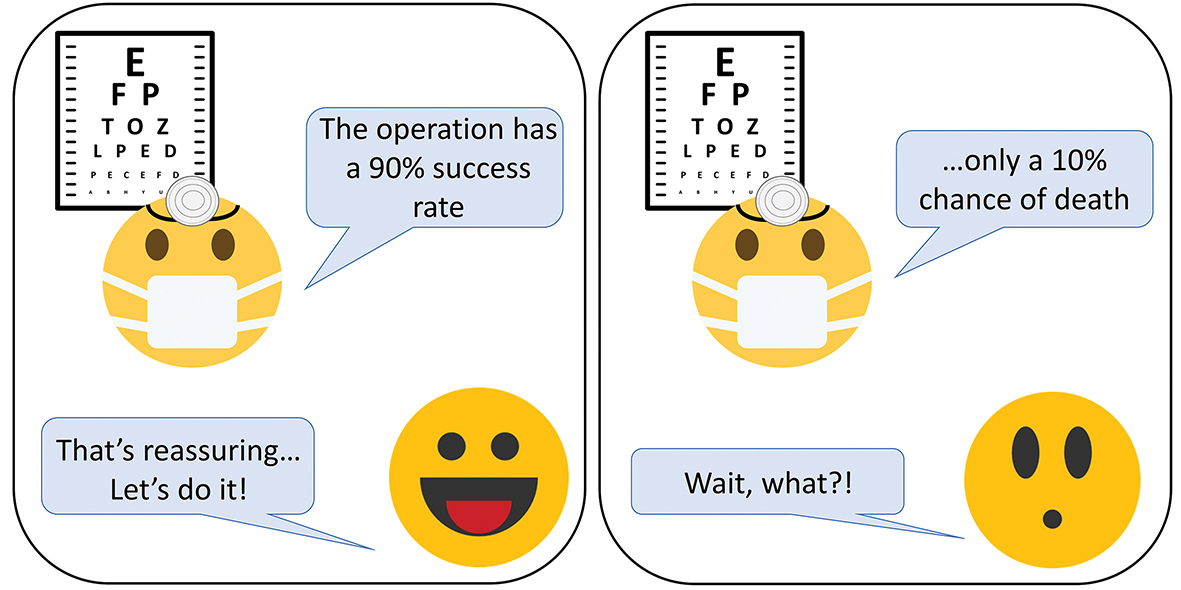

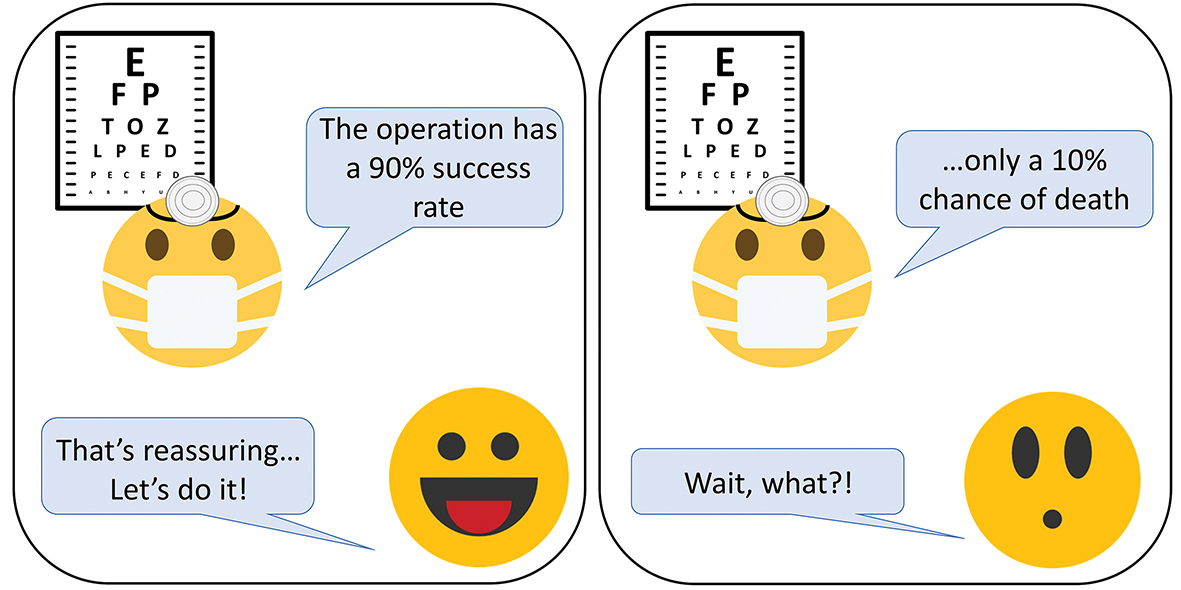

We know that how we talk about or “frame” information can have a big impact on the way people understand it, and how they respond to messages (Figure 1). Therefore, how we say something may be just as important as what we say. Although this has long been understood by advertisers and politicians,

it is not something that has often been practised within ecology and conservation.

Figure 1. Alternative ways of framing information can influence the ways an audience may respond to it.

Figure 1. Alternative ways of framing information can influence the ways an audience may respond to it.

2: Emphasise the things that matter to your audience (not necessarily what matters to you)

Strategically framing a message requires careful identification of the target audience, and understanding something about them and how best to engage them (Figure 2). Unfortunately, considering audiences in this way is not often done well in conservation, where all too often we pitch our messages primarily to those who already care.

Just because you care about protecting the habitat of a threatened species doesn’t mean that your target audience will, but other aspects of the issue may resonate with that audience (e.g., retaining natural areas for human recreation or wellbeing). You should also consider who/what might be the best messenger for that audience, as they will pay far more attention to some communication sources than others.

Figure 2. Issues should be framed to suit the audience you want to influence, for example, by focusing on the issues that will be of most importance or interest to them. This figure is based on a cartoon by Felix Schaad.

Figure 2. Issues should be framed to suit the audience you want to influence, for example, by focusing on the issues that will be of most importance or interest to them. This figure is based on a cartoon by Felix Schaad.

3: Use social norms

Social norms are the informal rules of “normal” behaviour within a particular social group, and strongly influence behaviour. For example, people are more likely to litter in an environment that is already littered,

as the discarded litter indicates this is normal behaviour in that environment.

Ensure, then, that what you emphasise in your messages promotes helpful norms. Specifically, you should emphasise desirable behaviour, and also social approval of the behaviour. By the same token, you should avoid emphasising undesirable behaviour, as this can indicate that such behaviour is “normal” and thus (unintentionally) promote it (Figure 3).

Deliberately leveraging social norms can be an effective strategy, and has been used to promote many different behaviours ranging from the re-use of hotel towelsto pro-health related behaviours and even

tax compliance (among many examples).

Figure 3. These menus are examples of how information can be framed to activate social norms, either helpfully or unhelpfully. Kuzzy’s menu communicates that making sustainable choices is normal behaviour for customers. At Sier’s this norm is paired with information about social approval of this behaviour, likely enhancing the influence of the message. In contrast, Henry’s establishes a norm of eating seafood regardless of how it is sourced, potentially encouraging this undesirable behaviour.

Figure 3. These menus are examples of how information can be framed to activate social norms, either helpfully or unhelpfully. Kuzzy’s menu communicates that making sustainable choices is normal behaviour for customers. At Sier’s this norm is paired with information about social approval of this behaviour, likely enhancing the influence of the message. In contrast, Henry’s establishes a norm of eating seafood regardless of how it is sourced, potentially encouraging this undesirable behaviour.

4: Reduce the psychological distance

Psychological distance is the sense of distance that people feel from themselves to another person, event or issue. When this is larger, people tend to think about the matter in a more abstract fashion, and may be

less motivated to take action.

Re-framing a message to reduce psychological distance can help engage the audience about an issue. Psychological distance includes geographic, temporal or social distance, and is also affected by the relative certainty of an event occurring (greater certainty reduces psychological distance).

A message framed to emphasise that a problem will affect people like the audience themselves, occur nearby and is highly likely to occur sometime soon will help reduce this distance (Figure 4).

One approach to increasing the vividness of a message is to evoke emotion. Emotive messages can be effective at motivating an audience, and may often be more influential than rational appeals.

However, when seeking to reduce psychological distance, you must take care not to make the situation seem

hopeless. This is a particular challenge for biodiversity conservation, given the complex and diffuse nature of many such problems. Hope-based appeals may be more effective at encouraging individual action.

Figure 4. The whale poster on the left communicates the issue as something far away (Antarctica) that has nothing to do with people’s lives (a whale in its natural state). In contrast, the poster on the right seeks to reduce psychological distance by: increasing the vividness; making the whale relatable to humans (i.e., the whale is making a plea for help, is crying); avoiding mention that the hunt is occurring far away; and seeks to engender a connection to the reader by referring to “our” whales.

Figure 4. The whale poster on the left communicates the issue as something far away (Antarctica) that has nothing to do with people’s lives (a whale in its natural state). In contrast, the poster on the right seeks to reduce psychological distance by: increasing the vividness; making the whale relatable to humans (i.e., the whale is making a plea for help, is crying); avoiding mention that the hunt is occurring far away; and seeks to engender a connection to the reader by referring to “our” whales.

5: Leverage useful biases

Biases that influence how we think and behave are called cognitive biases. There are many common types and if you are aware of them you can use them to your advantage or at least avoid ones that could unintentionally reduce the effectiveness of your messages.

For example, negative framing is often more effective at influencing people than the same message said in positive language (Figure 5).

Prospect theory results in a tendency for people to weigh losses more heavily than equivalent gains, so for environmental policy options “restored loss” tends to be seen

as more favourable than a “new gain”.

Other common biases to be aware of include: the scarcity heuristic, in which items or commodities perceived to be in short supply are considered more desirable and therefore more valuable; the endowment effect, in which people tend to value something more highly when they own it than if they do not; and the status quo bias, which is the preference to avoid change, so that when presented with alternatives, people display a bias for the status quo. (This is one reason why the “default” option is often a popular choice.)

Figure 5. Negative messaging is often more effective than the same message in positive language. In a study by Winter (2006), more than three times as many hikers who encountered the positively framed sign disobeyed the request to stay on the path.

Figure 5. Negative messaging is often more effective than the same message in positive language. In a study by Winter (2006), more than three times as many hikers who encountered the positively framed sign disobeyed the request to stay on the path.

Final note

Framing is no silver bullet and should always be considered for a given audience and context. Nonetheless, these proven general principles will help you begin to strategically frame your messages for greater effect.

Work cited

Kusmanoff AM, Fidler F, Gordon A, Garrard GE, Bekessy SA. 2020. Five lessons to guide more effective biodiversity conservation message framing. Conservation Biology. DOI: 10.1111/cobi.13482

Further information

Alex Kusmanoff - alex.kusmanoff@rmit.edu.au