The importance of community for threatened species

Wednesday, 21 October 2020Threatened Species Recovery Hub Deputy Director Professor Stephen Garnett from Charles Darwin University reflects on the importance of the community in threatened species conservation, from passionate volunteers to vast numbers of people making small changes that collectively add up to big wins for Australian nature.

The mosquitoes were dreadful, the route steep and unmarked, and the rainforest uncomfortably dense – but there was triumph in this morning’s message about a recent trip to the top of Mount Elliot, a high, isolated peak south of Townsville. The trio of birdwatchers had found display courts of tooth-billed bowerbirds, an upland species at risk from rising temperatures. The expedition also completed the first comprehensive survey of the species, documenting the location of 650 active courts.

Dom Chaplin and his friends are not professional scientists or conservation managers. Rather, they are part of the multilayered community commitment to nature that makes all threatened species conservation possible.

Tooth-billed bowerbird. Image: Dominic Chaplin

Tooth-billed bowerbird. Image: Dominic Chaplin

Valuable volunteers

Such support takes many forms. Dom and his friends may have more energy and endurance than most, but they are not alone. Many enthusiastic volunteers contribute to surveys and monitoring. Birdwatchers are probably the best organised group, with BirdLife Australia and other platforms providing a ready means of assembling observations. However, knowledge of the rarest fish and reptiles described in Issue 17 of Science for Saving Species would be far less complete but for the contributions of volunteer naturalists. In a similar exercise on butterflies, nearly every expert was an amateur naturalist with a passion for their subject and an extraordinary level of expertise in butterfly natural history.

In a sense, the paid professionals also provide a form of community support that is often overlooked. Few conservation managers see their work as just a job. On the contrary, their chosen career is a vocation, with the salary forming just a part of their deep personal commitment to retaining our biological inheritance.

Many people in government conservation agencies dedicate their careers to threatened species conservation, sometimes putting aside opportunities for professional advancement to remain close to species they have come to love.

Community support is often provided in partnership with professionals for the active management of many species. Such partnerships were a common thread in the hub’s book on conservation success (Recovering Australian threatened species: A book of hope). Nest boxes are built and erected for hollow-dependent species, forests planted, weeds pulled, habitat fenced. Outside funding often contributes to the costs of materials but the labour is entirely voluntary, and worth far more because money cannot buy passion for a cause. Involvement in such activities further deepens the bond between the human community and the threatened species with which they live. People can return years later to a replanted forest and witness with pride the grown trees that they first knew as tender seedlings.

Pittsworth District Landcare Association are important champions for the Condamine and Roma (shown) grassland earless dragons, which are among Australia’s most threatened reptiles. Image: Stephen Zozaya

Pittsworth District Landcare Association are important champions for the Condamine and Roma (shown) grassland earless dragons, which are among Australia’s most threatened reptiles. Image: Stephen Zozaya

The power of numbers

Community support can also be more passive. In this Issue 17 of Science for Saving species is an article on the destruction wrought by domestic cats. Many people need no persuasion to keep their cat at home. They love Tabitha, but they love wildlife too. Drivers slow down for the sake of cassowaries. Farmers leave forest fragments for the sake of threatened plants. An awareness of threatened species nudges people towards empathetic behaviour. Not everyone can become actively involved, but surveys have shown that the vast majority of Australians do not want more extinctions.

Similarly, for Indigenous people, threatened species conservation is often not an end in itself but rather an emergent property of culturally driven caring for Country. Well-nurtured Country will keep its full quota of species and, as sometimes new threats have arisen, new skills need to be learnt. As with the story of Mankarr in Issue 17 of Science for Saving Species), threatened species can also act as conduits for old knowledge from a time when the animals were not threatened at all.

Meaningful engagement between Western scientists and Indigenous communities leads to better outcomes for threatened species; as a hub we are working to support researchers and institutions to work with Indigenous people in a culturally respectful way (Issue 17 of Science for Saving Species).

Pittsworth District Landcare Association has coordinated community surveys of paddocks and road verges for the Roma and Condamine dragons, raised awareness and promoted sustainable farming practices to support the survival of the lizards. Image: Pittsworth District Landcare Association

Pittsworth District Landcare Association has coordinated community surveys of paddocks and road verges for the Roma and Condamine dragons, raised awareness and promoted sustainable farming practices to support the survival of the lizards. Image: Pittsworth District Landcare Association

Tangible support

The ultimate form of community support is political. Once naturalists wrote wistfully about the inevitable loss of species in the face of “progress”. However, over the past 50 years, more and more Australians have recoiled from the idea of losing nature, particularly threatened species. Of course, as is proper in a democracy, ideas are contested – but legislation to protect threatened species, and investment into research and management, would never have happened without a broad shift in community attitudes.

In some ways the effectiveness of a country in retaining its full complement of species can be seen as a measure of its overall success – a proxy measure of its wealth, its governance and its commitment to a long-term future – in short, a measure of the quality of its society.

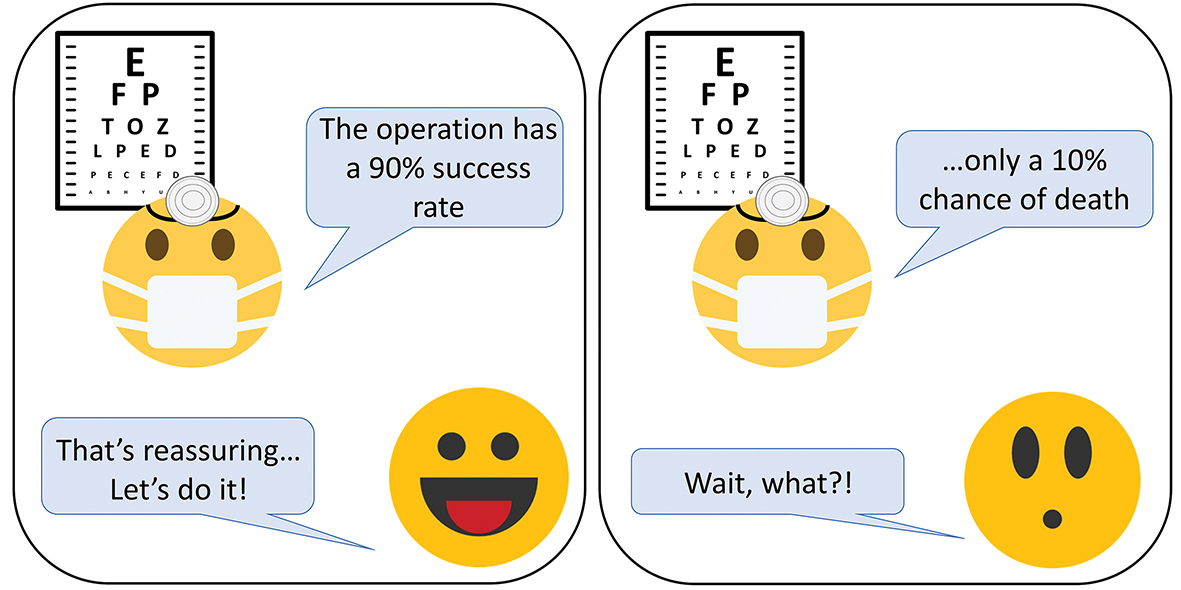

Overall, threatened species conservation provides a tangible expression of the community’s love of nature, and fear of its loss. Alex Kusmanoff and colleagues talk in their article (Issue 17 of Science for Saving Species) about the role emotional connection plays in messaging. Many abstract notions in conservation – landscapes, biodiversity, threatening processes – have little resonance in the

hearts of the broader community. A personal bond with threatened species is far more powerful, and the product of a long history of communication about species scarcity, the intrinsic value people place on rarity and the finality of extinction.

Back on Mount Elliot, long-term climate scientist/biologist Stephen Williams has described climbing the 1218 m mountain as among “the hardest walks I have done on any mountain here or elsewhere in the world”. Threatened species continue to provide motivation for enormous effort and deep commitment.

Mt Tyson Landcarer Paula Halford (right) with representatives of Ergon Energy which cosponsored the production of chocolate Condamine dragons by local confectioner White Mischief as part of an awareness and fundraising campaign. Funds raised supported essential research for the Condamine dragon by Museums Victoria. Image: Pittsworth District Landcare Association

Mt Tyson Landcarer Paula Halford (right) with representatives of Ergon Energy which cosponsored the production of chocolate Condamine dragons by local confectioner White Mischief as part of an awareness and fundraising campaign. Funds raised supported essential research for the Condamine dragon by Museums Victoria. Image: Pittsworth District Landcare Association

Further reading

Further information

Stephen Garnett - stephen.garnett@cdu.edu.au

Top image: Birdwatchers like Dominic Chaplin have collected vast amounts of valuable survey data across Australia. This photo was taken during a tough walk up Mount Elliot to survey display courts of tooth-billed bowerbirds. Image: Dominic Chaplin

-

Australia’s possums and gliders

Tuesday, 09 July 2019 -

Backyard scientists helping possums and gliders

Tuesday, 26 November 2019 -

CAUL Urban Wildlife app Possums and Gliders Project

Friday, 24 May 2019 -

Citizen scientists collaborate on mammal surveys in urban gardens

Tuesday, 29 January 2019 -

Citizen, where art thou?

Monday, 07 August 2017 -

Editorial: It is people who save species

Thursday, 15 December 2016 -

Georgia Garrard - Connecting people with biodiversity

Tuesday, 12 March 2019 -

Holding on to what's golden

Tuesday, 11 October 2016 -

Seize the day

Monday, 07 August 2017 -

Threatened species in city spaces

Sunday, 12 March 2017 -

Wineries for ringtails

Thursday, 02 July 2020 -

The best way to harness people power

Tuesday, 24 May 2016 -

5 lessons for more effective conservation messaging

Wednesday, 28 October 2020