The best way to harness people power

Tuesday, 24 May 2016While local communities can play an important role in threatened species recovery, and scientists make significant efforts to involve locals in recovery efforts, there isn’t yet a lot of science around the best way to engage them.

“Most recovery plans include funds for community engagement but there is virtually no research on the most effective approaches – most money is spent on the basis of the hunches of managers,” says Dr Georgia Garrard, who leads Project 6.3 with Dr Sarah Bekessy.

With the help of ecologists, social scientists, economists and psychologists, Project 6.3 will research the best ways to deliver conservation messages and educate communities.

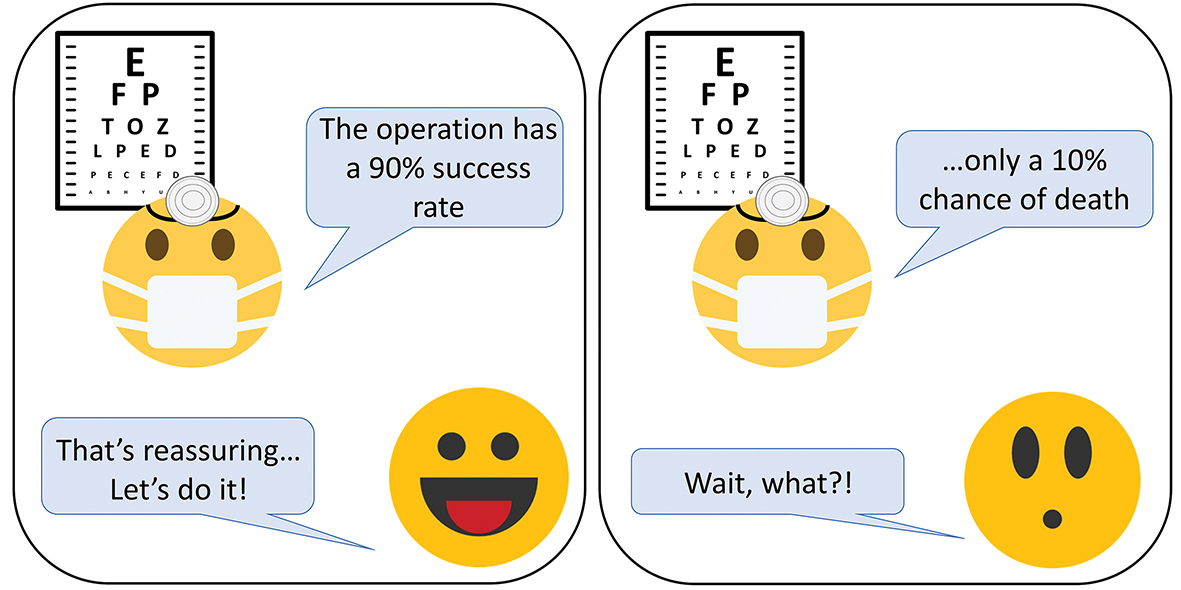

“There is a constant bombardment of bad news about threatened species – which species will be lost and how many are threatened. But this might not be the best approach,” says Dr Garrard.

“There's now evidence to show that when you frame messages in a positive way, when you educate people around what they can do and the positive impact they can have, it makes them feel more empowered and therefore more likely to act.”

One of the first areas to explore will be communications and messaging around fire.

“Fire is a really vexed topic. Emotions rise when people talk about fire because it's a natural process in certain ecosystems but can also be a destructive process - it’s both a saviour and a threat to some species.”

“We’ll research the sort of language used about fire - what it means to different people and how we talk about fire in the cities as opposed to how we would talk in remote Australia. This will help us have better conversations with stakeholders and land managers around burning programs.”

As well as examining the best messaging to inspire conservation action in the community, the next step for Project 6.3 will be to set up a conservation opportunity workshop with the brightest minds from - and outside - the conservation field.

“We can see a lot of exciting and novel partnership opportunities arising as a result of changes in technology, society, the economy and environment. For example, mobile phone-based citizen science could provide better monitoring data, and carbon investment could be used to drive habitat restoration.”

“As well as conservation scientists, we’ll invite potential partners who think way outside of conservation to help identify other trends which may present in the near future. We’ll be

bringing in people from completely different disciplines like futurists or strategic specialists. It's pretty exciting.”

The project will also look at how communities might be encouraged to buy-in to the conservation of non-charismatic species, which can be a challenge.

“There are hundreds of threatened plant species in Australia that don't necessarily have the same public appeal as a koala or the orange-bellied parrot. For example, there's a whole bunch of critically endangered native grasses and herbs out in the grasslands that could do with more public affection.”

A better understanding of how to increase community support for threatened species recovery will be hugely beneficial for environmental groups as well as government.

“We know the success of conservation in urban areas is really enhanced by having a community who feels stewardship over that area.”

“For example, one of the best native grassland remnants that we know of is in Sunbury, which thrived because there was a very strong community group (Friends of the Evans Street Native Grassland) who got behind it. They were instrumental in its protection, which led to ongoing support from the local council.”

The project will also look at how to measure the effectiveness of community engagement and environmental education programs, which can be difficult.

“Some of the knowledge that we already have suggests that these programs provide social and learning benefits, but the environmental benefits often aren't as clear and are often indirect in nature.”

“Learning about their local ecosystem may build social capital in the community and translate into a more environmental ethic - but it doesn't necessarily translate to them behaving differently toward that ecosystem. We want to better capture the benefits that arrive from these programs.”

-

The importance of community for threatened species

Wednesday, 21 October 2020 -

Editorial: It is people who save species

Thursday, 15 December 2016 -

Georgia Garrard - Connecting people with biodiversity

Tuesday, 12 March 2019 -

Holding on to what's golden

Tuesday, 11 October 2016 -

Threatened species in city spaces

Sunday, 12 March 2017 -

5 lessons for more effective conservation messaging

Wednesday, 28 October 2020